By Sally-Anne Shearn

In June 1845, The

Morning Post reported that the residents of Loughborough had been witness

to an ‘imposing spectacle’ of a funeral, ‘amid

rites and observances of a nature so unusual as to well merit the fullest notice’.

The deceased was Lady Mary Anne Arundell, the widow of James, 10th Baron

Arundell of Wardour Castle, and the observances were Roman Catholic, presided

over by the Italian Father Pagani, Superior of nearby Ratcliffe

College.

The

funeral, and the rather saintly qualities of Lady Arundell, was reported on in

great detail in The Tablet, a Catholic paper, as well as The Morning

Post, but another source of information about the life and death of Lady

Arundell, and her contributions to Loughborough, exists at the Borthwick

Institute for Archives, thanks to the survival of the letters of her ‘most

attached’ friend Henrietta Crewe. Henrietta’s letters to her sister and

confidante Annabel Crewe, later Annabel Milnes, wife of Richard Monckton

Milnes, 1st Baron Houghton, provide a window into the life and personality of

Lady Arundell, her decision to move to Loughborough, and the events that

followed when she set out to bring an Italian convent and school to a small

Leicestershire town.

Lady

Mary Anne Nugent-Temple-Grenville was born in 1787, the only daughter of the

1st Marquess of Buckingham and a granddaughter of George Grenville, Prime

Minister between 1763 and 1765. Although her father, the Marquess, was a

Protestant, an 1886 Life of Antonio Rosmini Serbati, Catholic priest,

theologian, and founder of the Institute of Charity, claims that her mother,

Mary Nugent, the daughter of the Irish Viscount Clare, was Catholic and that it

was by her example that the young Lady Mary was first introduced to the faith.

|

Lady Mary Anne Nugent-Temple-Grenville by John Hoppner (19th

century) Wikimedia Commons |

She

converted formally to Roman Catholicism in 1810 and in 1811 she married the

Catholic James Arundell, then heir to the 9th Baron of Wardour. He

succeeded as the 10th Baron in 1817. Lady Arundell and her husband travelled

widely on the continent, and it was in Italy in the early 1830s that they made

the acquaintance of Rosmini himself and were first introduced to his Institute

of Charity. The institute was then still in its infancy, having been

founded in 1828. It was dedicated to charitable work in all its forms but

focused particularly on pastoral and spiritual care, education, and care for

the sick, poor, and marginalised, work that greatly appealed to Lady

Arundell. The Institute was approved formally as a religious congregation

by Pope Gregory XVI in 1838.

Rosmini

wrote to Lady Arundell personally in 1834 when Lord Arundell died unexpectedly

at Rome, leaving her a widow at the age of only 47. She returned to

England alone, and at some point in the next few years moved to Bath to take up

residence at Prior Park, the Roman Catholic college established by Bishop Peter

Augustine Baines in 1828. There too, she found the influence of Rosmini,

who had sent members of his Institute to teach at the college at Baines’ request.

The first was Father Luigi Gentili, followed later by Dr Pagani. A novice

from Ampleforth Abbey who studied at Prior Park, Moses Furlong, would also

later join the Institute and become spiritual advisor to Lady Arundell.

|

| Francesco Hayez, Ritratto di Antonio Rosmini (1853) Wikimedia Commons |

It

seems to have been at Prior Park that Lady Arundell met and became friends with

Henrietta Crewe. Despite their differences in age (Henrietta was 21 years

her junior), the two women had much in common. Like Lady Arundell,

Henrietta was born to a wealthy and well-connected Protestant family, she was

the granddaughter of the 1st Baron Crewe and his wife Frances Anne Greville,

and she was also a convert to the Catholic faith. Between 1829 and 1836

she had lived at Liège in Belgium with her estranged

father, the 2nd Baron Crewe, and it was here that her interest in the Catholic

faith led her not only to convert but also to make plans to join a convent - an

ambition which was ultimately forbidden by her family.

Henrietta

had already made several visits to Prior Park in the early 1830s during her

regular trips back to England, but in 1836, following the death of her father,

she returned to England for good and took up residence at The Priory, a house

in the grounds. In these decades Prior Park would seem to have been

something of a haven for a small circle of well-bred Catholic ladies who were

regular visitors, staying either in Bath or at the college itself, and deeply

devoted to the colourful and charismatic Bishop Baines. Some, like

Henrietta, even invested money in the enterprise, although few saw a return on

their investments. It is not clear from Henrietta’s letters when she and

Lady Arundell first met. In a letter of 1841 Henrietta mentions Lady

Arundell’s visit of two years previously ‘before she had been quite able to settle

about returning.’

Evidently, she had

made up her mind by May 1840 when Henrietta writes of her familiarly as a

fellow resident and close friend. The accounts of Lady Arundell’s funeral

describe her as a ‘rigid Catholic’, living a life of ‘extraordinary self-denial

and charity’, but it is clear from Henrietta’s letters to her sister that she

was far more than this rather pious epithet suggests. Attempting to sum

up her ‘darling friend’ in 1843, Henrietta writes of the ‘freshness, & originality,

& fun, & supremely delightful nonsense of her’, recalling ‘happy Monday

evenings’ spent together reading aloud from the latest serialised novel by

Charles Dickens, long conversations that ‘she always contrived to render

merry’, and regular lively visits from her younger brother Lord Nugent and his

family to whom Lady Arundell was very close. ‘There never was such

an attachment,’ Henrietta had written in an earlier letter, ‘as between that

brother & sister’.

But Lady Arundell

could not be fully content with her life at Bath, busy and enjoyable as it

was. As she revealed to Henrietta, she had long cherished hopes of

founding a convent in England and perhaps even joining it herself. She had

talked of it with her husband during their marriage and they had both agreed

that whoever should survive the other would embrace a religious life, she as a

nun of some sort and he as a Jesuit. Her plan was initially to establish

a convent near Bath, where the sisters could run a school for the poor, but finding

an affordable house proved difficult and her choice of religious order

unexpectedly contentious. Bishop Baines, according to Henrietta, favoured

the Sisters of Charity or Sisters of Mercy, but Lady Arundell had her heart set

upon the Italian ‘Suore della Providenza’ or Sisters of Providence of Rosmini’s

own Institute of Charity, commonly known as the Rosminian Sisters of

Providence.

It is likely there

was more to Baines’ opposition than Henrietta knew or wished to reveal to Annabel,

who had a persistent suspicion of all things Catholic. By 1840 the

relationship between Baines and Rosmini was strained. Baines’ biographer

Pamela J. Gilbert characterises Baines as something of a flawed genius, a

brilliant educationalist but obstinate, antagonistic, and as likely to create

enemies as loyal followers like Henrietta. It was certainly so with

Rosmini and his followers at Prior Park. When admission numbers began to

fall in the 1830s Baines blamed the strict regime introduced by Father Gentili

and set about limiting his authority and finally removing him from the college

altogether. In 1838 he sent him to a convent at Stapehill and then to

another at Spettisbury near Blandford. Rosmini

was forced to appoint the relative newcomer, Dr Pagani, as Superior of the

Institute at Prior Park in his place and withdraw Gentili back to Italy.

After a brief period there however, Rosmini sent Gentili to England to take up

residence as chaplain to Ambrose Lisle March Phillipps, a Roman Catholic convert,

disliked by Baines, who was active in the Catholic revival movement in

England. From Phillipps’ home at Grace Dieu manor, near Loughborough,

Gentili ran a hugely successful Catholic mission and was credited with

converting several hundred people to the faith. In August 1842 Rosmini

took the decision to withdraw all remaining Rosminian brethren from Prior Park

and to establish a new foundation in Leicestershire in the Midland

District. Fathers Pagani and Furlong left Prior Park later that month and

joined Father Gentili in Loughborough at the first house of the Institute of

Charity in England.

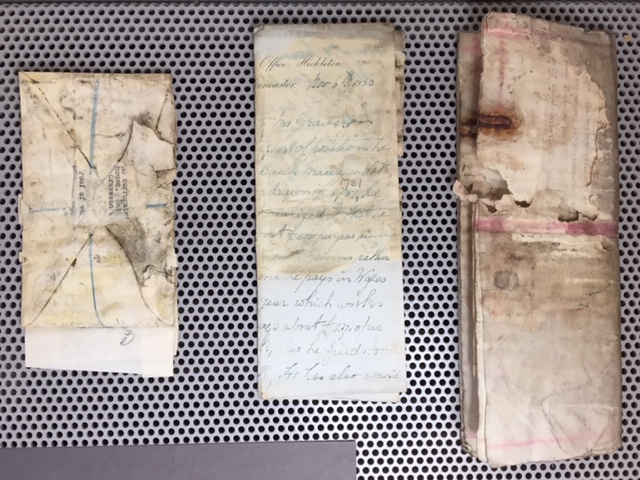

|

| Letter 243 from Henrietta Crewe to Annabel Crewe, Milnes Coates Archive |

It is perhaps

unsurprising then that when Lady Arundell’s plans for a Bath foundation were

abandoned she would turn her attention instead to Loughborough, now the centre

of Rosminian work in England. In March 1843 Henrietta was finally able to

write to her sister to reveal all, for ‘the embargo has been taken off and my

lips unsealed - Before...I was under both orders and a promise not to mention

it to any one.’ Lady Arundell had indeed settled upon ‘the little

stocking-weaving Town’ of Loughborough for her convent. The presiding

Bishop, Bishop Walsh, had no objection to Lady Arundell’s choice of religious

sisters, Rosmini himself approved, and a house was found ‘in every respect

adapted to the purpose’ and evidently cheaper, ‘financial difficulties’ being

‘not so great in that neighbourhood’.

Lady Arundell left

Bath on the 22nd of February and Gilbert writes that Baines felt Lady

Arundell’s defection from the college sorely, although Henrietta describes how

the Bishop appeared at the door of Prior Park at the last moment to give her

his blessing. Her leaving was evidently a painful subject for Henrietta,

and for Lady Arundell too who wrote that no words could express what she felt

and always should feel on the matter. ‘I, who have so few friends! at

leaving one who I feel is one of the best!’

After a stay of

several weeks with the Phillipps’ family at Grace Dieu, Lady Arundell finally

took possession of her new home in Loughborough. She wrote to Henrietta

soon after her arrival and regularly thereafter. Her first weeks were

spent ‘shopping- furniture-buying, & arranging’ the house, in what she

unfortunately calls the ‘worst & roughest paved town in England’. She

was accompanied there by her butler and cook, a Mr and Mrs Doughty who had been

in her service for more than thirty years. The house was called Paget’s

House and was situated on Woodgate. After

her first visit later in 1843 Henrietta described it to Annabel. It was a

half modern, half Elizabethan house with ample accommodation for a community of

six or eight Sisters of Charity, besides Lady Arundell’s own apartment, and a

room which had been converted into a chapel for daily mass. Lady

Arundell’s drawing room and bedroom looked out over the ‘quiet shady garden’ at

the rear of the house ‘where the Sisters will be able to breathe a little fresh

air and recreate from their labours being unlooked’. At present the

garden was only a lawn but Lady Arundell had plans to plant some flower beds in

the autumn. The garden door opened on to a road leading into the country

and the country thereabouts was, to Henrietta’s unflattering surprise,

‘extremely pretty - the whole district of Charnwood Forest forming a sort of

oasis in the otherwise ugly county of Leicestershire’.

By Henrietta’s second

visit Lady Arundell had made a few additional alterations, particularly to her

drawing room where she had created a little greenhouse ‘full of flowers and birds’

with the ‘prettiest effect imaginable’ by adding a second sheet of glass in

front of the lower half of the large window. The addition was practical

as well as pretty for Henrietta reports that the rest of the house was

noticeably cold, with no carpets due to ‘Conventual simplicity’.

Henrietta greatly

enjoyed her first visit to Loughborough in September 1843. As well as seeing the new house, she visited

Grace Dieu and met the ‘cheerful’ and welcoming Phillipps family, dined with

Lady Arundell and Father Gentili (‘a very superior person’ as she wrote to Annabel)

and saw the new Catholic church at Shepshed, designed by Augustus Pugin. She also drove out to the recently founded Cistercian

monastery at Mount St Bernard, whose permanent buildings were also designed by

Pugin. It was a place she had long

wished to see, and she professed herself even more gratified than she had

expected at the sight of the flourishing farm amidst the ‘smiling landscape’

and the charitable works of the brothers, a much needed alternative, in her

eyes, to the grudging aid offered by the union workhouses.

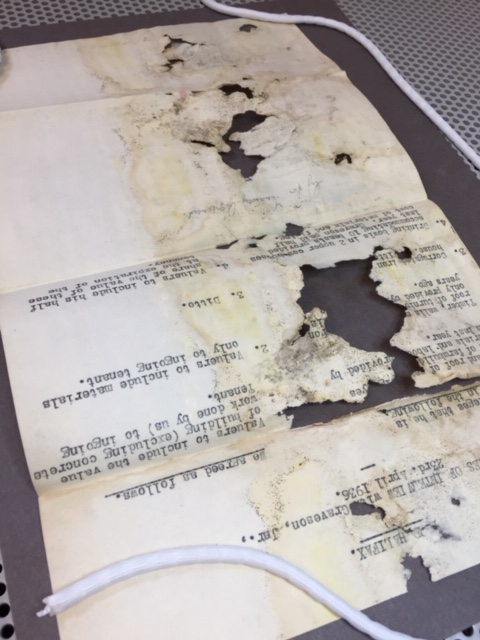

|

| The Milnes Coates Crewe correspondence |

She was disappointed

however, on this occasion, not to meet any of the Sisters of Providence who

were to labour alongside Lady Arundell. The

two ‘ladies from Milan’ chosen by Rosmini to begin the convent and run the

school, Sister Maria Francesca Parea and Sister Maria Anastasia Samonini, were

still ‘waiting for a boat’ and would reach Loughborough the following month

after a journey of twelve days. It was in mid-October then that two Roman

Catholic nuns appeared on the streets of Loughborough for the first time in

their black habits and stiff white veils, to the outrage of many of the town’s

Protestant residents. ‘Already they have been obliged to have black poke

bonnets and veils concocted for going out of doors’, Henrietta wrote just a few

months later, ‘as the three times that they ventured forth in their white head

gear, they were regularly mobbed.’ The last time was ‘the worst of all,

and the poor little things were a little frightened as well as incommoded by

the crowd’ that the change of clothing was deemed a necessity.

By the time Henrietta

met the nuns in person in early 1844, they were settling into their new

life. Henrietta reports that the elder of the two, Superiora, was still

struggling with the language, but the younger, Suor Anastasia, was making better

progress. They already had two English postulants, a widow and a young

girl, who would soon commence their novitiate. The first postulant took

the habit on the Feast of the Annunciation in 1844 and the small community began

its life with Suor Maria Francesca as Superior and Suor Anastasia as Mistress

of Novices.

The nuns formally

took charge of the school in March 1844, becoming the first religious sisters

to run a Catholic day school in England in the nineteenth century. An

article in the Catholic Herald in 1985 provides some details as to the

layout of the school. Lady Arundell had adapted the stables of the house

for an infants’ school and made the loft above the coach house into a classroom

for the older girls. Before the nuns took charge, lessons were being

given by a Mrs Moon, a ‘kind mistress’ who Henrietta notes had ‘the best that

Loughbro’ could supply, but very far from what is requisite’, and Lady Arundell

herself who devoted an hour or two each day to it. Now the nuns would

begin to teach the school ‘according to their own method’, although given the

language barriers Henrietta writes that they accepted there might be a few

‘spropositi’ (an Italian word for blunders) along the way.

Whatever spropositi

there might have been, the school and convent continued to grow and to thrive,

particularly after the arrival of Mary Barbara Amherst as a postulant in

1845. The sister of the Bishop of Northampton, as Mary Agnes Amherst she

would become the first English Superior of the Sisters of Providence and a

central figure in the growth of the order’s work in England.

Sadly, Lady Arundell

would not live long enough to see these developments. She died in June

1845, only two years after her arrival in the town and before she had seen her

dream of erecting a proper convent building realised. On hearing of her

friend being suddenly taken ill, Henrietta immediately set out for Loughborough

but arrived too late. ‘You did not, could not know how very dearly I

loved her’ she wrote to Annabel that night, from her room at the convent, ‘or

how immense a loss it is to me’. She describes the arrival of Lord

Nugent, whose ‘voice and manner’ she would never forget, and the long and

arduous day of her funeral when she resolved to follow her ‘darling Mimi’ with

her prayers to her last resting place. She couldn’t help but note that the

route along the streets to the little Catholic chapel was the same one they had

so often trodden together to attend prayers. Lady Arundell left money

to continue her work in Loughborough and instructions to be buried at the

nearby Ratcliffe College, recently established by Rosmini and Father Gentili.

After Lady Arundell’s

death Henrietta mentions Loughborough only rarely, but it is clear she kept up

with the progress of her friend’s work there and in 1848 she made another

visit. Writing afterwards from her brother’s grand home at Crewe Hall in

Cheshire she calls the busy house party there her ‘little penance after the delights

of dear Loughboro’. In answer to Annabel’s concern, she assures her that

‘it is scarcely sad to go there, my dearest, I cannot explain to you what it is

- I only know that it is luxury. I feel as if I had her still when I am in

those darling scenes where we have so often prayed together - where we last

parted - where she still lives in all these good works which it has pleased God

to bless in so very wonderful a manner’. To Henrietta’s delight ‘her

Nuns’ had increased in number from 3 to 17 and a ‘charming convent building’ was

being built just out of the town, on the Park Road.

Our Lady’s Convent

School would open in 1850 and today, more than 170 years on, the work begun by

Lady Arundell and the Italian sisters lives on as Loughborough Amherst School.

Bibliography

Milnes Coates Archive, Borthwick Institute for Archives

‘Importing the Rosminians’, in The Catholic Herald, 25 October 1985

Sister Maria Bruna Ferretti, The Rosminian Sisters of Providence, ed. J. Anthony Dewhirst (2000)

Pamela J. Gilbert, This Restless Prelate: Bishop Peter Baines 1786-1843 (2006)

William Lockhart, Life

of Antonio Rosmini Serbati, Founder of the Institute of Charity, Volume II

(1886)

John Morris, A

Selection from the Ascetical Letters of Antonio Rosmini, Volume II 1832-1836

(1995)