_________________________________________________________________________________

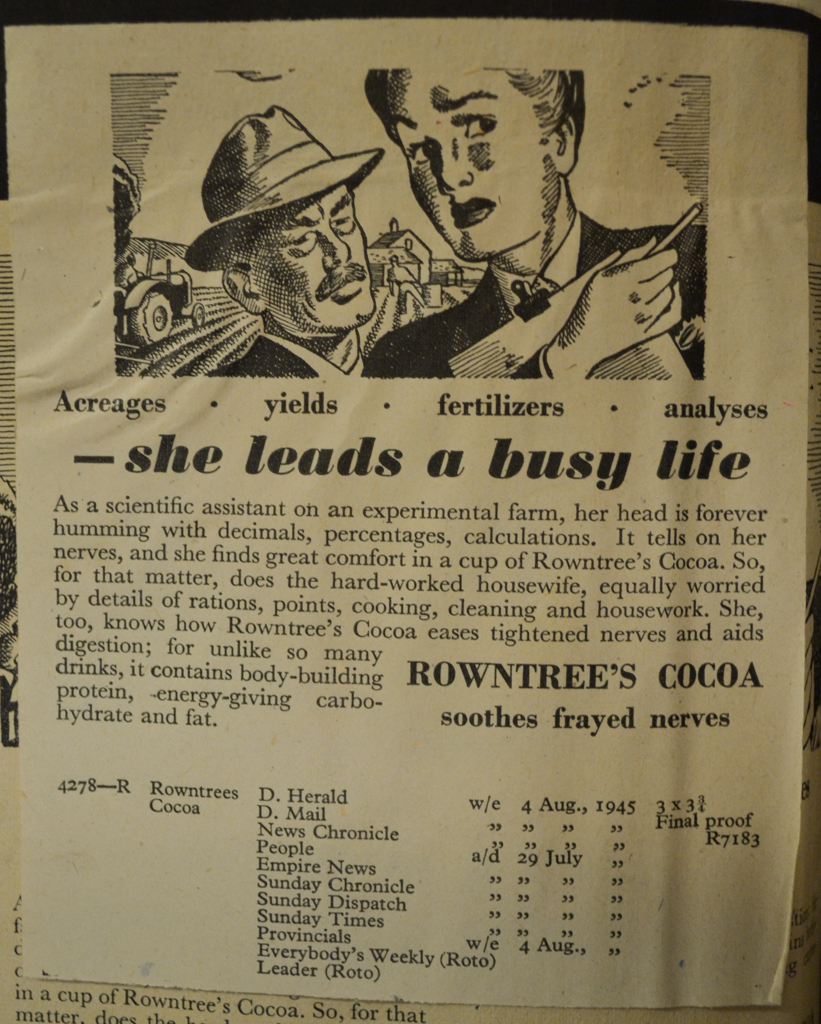

In spring 1939, John W. Harvey, professor of philosophy at Leeds University and a prominent Quaker, wrote to Dr. Arthur Pool, Medical Superintendent at the Retreat Hospital, requesting help in finding work and hospitality for a ‘very distinguished’ émigré psychoanalyst who had fled Vienna in the aftermath of the Anschluss. The letter, preserved in a file of correspondence and papers in the Retreat Archive at the Borthwick institute relating to applications for posts by European refugees before and during the war (RET/5/6/16), explains that not only had Dr. Maxim Steiner ‘heard of the Retreat’, but came ‘with very strong recommendations from Prof. Freud’, to whom Steiner acted as physician and dermatologist in Vienna.

|

| Letter from John W. Harvey, University of Leeds to Dr. Arthur Pool concerning Dr. Maxim Steiner, April 1939. |

While Steiner was not ultimately able to secure work at the Retreat, he was in no sense the only physician to seek refuge from Nazi persecution in the UK or, indeed, at the Retreat. A Quaker poverty relief unit had been active in Vienna for some years, and Freud himself had dined at the Friends Society there, likely through acquaintance with British Quaker psychoanalyst John Rickman. Rickman had moved to Vienna in 1920 and, with his wife Lydia, spent much time working with the unit to alleviate poverty. In fact, the Friends War Victims’ Relief Committee (later the Friends Relief Service) had acted to organize aid and hospitality for Europeans affected by poverty, war and political instability since the Franco-Prussian war in 1870, and was ultimately awarded the Nobel peace prize in 1947 for its wartime work.

|

| Photograph of Arnold S. Rowntree with Dr Arthur Pool, Retreat Physician Superintendent, 1946. |

Little correspondence survives regarding the successful arrival in April 1939 of Dr. Siegfried Kiewe, but Management Committee minutes tell us that he had been forced to leave Berlin ‘on account of his being a Jew’. The Committee offered hospitality ‘for an indefinite period’, and psychiatrist and family were lodged with Retreat secretary Mr. Burgess at Garrow Bank. Kiewe initially undertook laboratory, dispensary and massage work at the hospital, but in 1941, the Committee and Board of Control approved his undertaking of locum duties, and he continued thereafter as a salaried Assistant Physician until retirement in January 1959. Upon receipt of the Alfred and Margaret Torrie award, given to staff making an outstanding contribution to the wellbeing of patients, Kiewe payed tribute to the ‘kindness, understanding and tolerance’ he had received from the moment of his arrival in York. He died in 1986 at the age of 105.(2)

Dr. Fritz Kraupl, a medical dietician from Sudetenland exiled in London with experience of treating nervous disorders, was initially invited to the Retreat as a guest of the Committee with the intention of undertaking a kitchen traineeship. However, the committee felt that it would be inappropriate to place a male physician into a kitchen in which the ‘staff are wholly female’, and having taken up residence on 31st July 1939, Kraupl was found work in the Retreat laboratory, before obtaining a Clinical Assistant post at the Crichton Royal, Dumfries, in May 1940.

Securing safe passage for Dr. Rudolph Koch, however, proved more difficult. The Vienna Society of Friends approached Pool in November 1938 seeking hospitality and work for a physician ‘just been released from the concentration camp’. In correspondence, Koch declared himself ‘compleatly [sic] healthy and willing to work’, but stressed the need to escape from Vienna with the ‘utmost urgency’. Given the prohibitive implementation of the UK’s immigration legislation under the 1919 Aliens Restriction Act and Aliens Order 1920, which severely limited the possibility of refugees gaining employment, Pool was unwilling to try to engage Koch as a physician. Instead, he submitted a formal request to the Home Office for permission to employ a ‘foreigner who has left or wishes to leave Germany or Austria on political, racial or religious grounds’ as a laboratory technician. The combination of an intensifying climate of Home Office suspicion and the delay in processing applications due to a huge increase in numbers of applicants, however, took its toll on the Koch family. This is most clearly felt in the series of increasingly desperate letters from Koch’s mother preserved in the correspondence file, who wrote directly to Pool to express ‘the greatest worry about my son’.

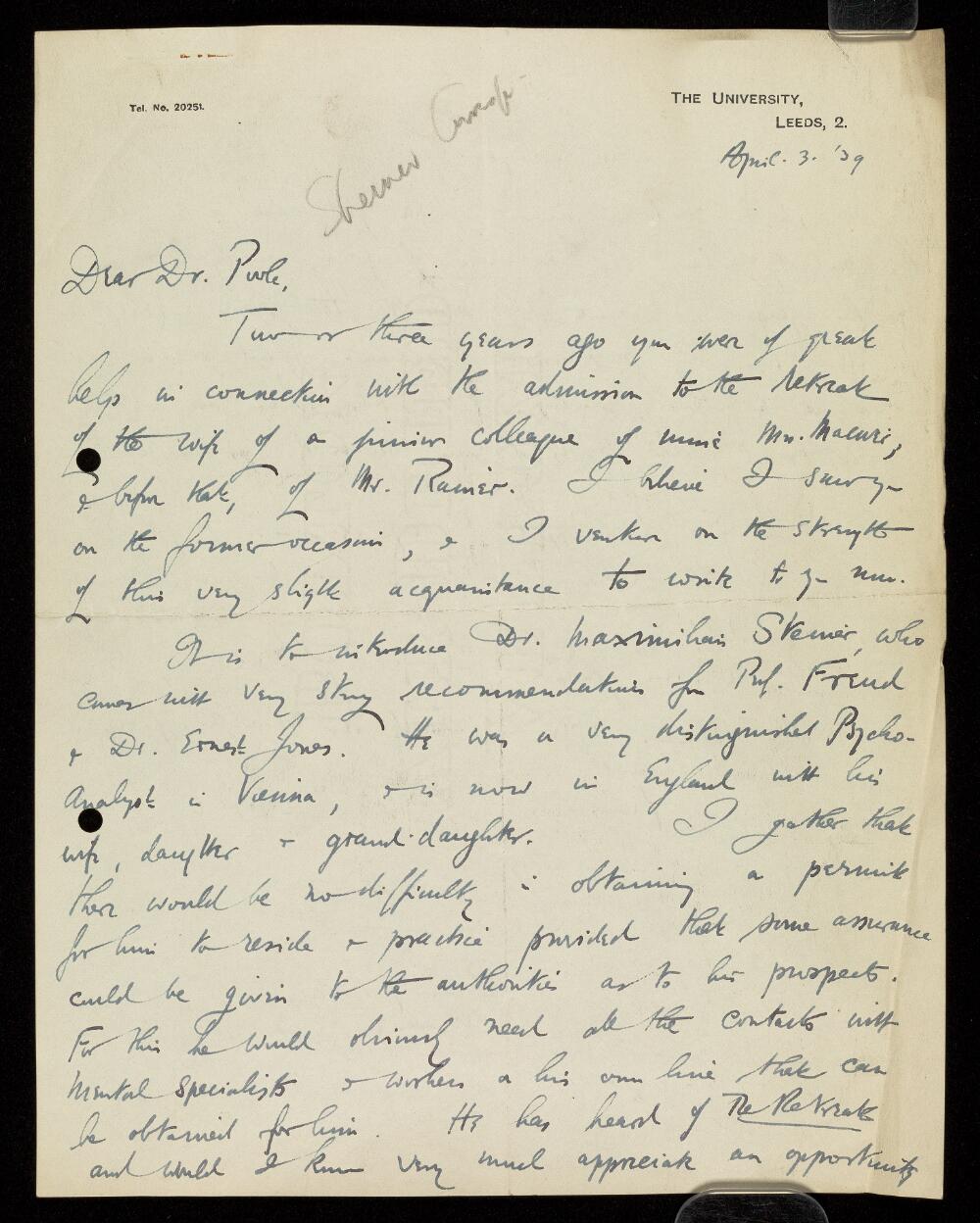

Despite Pool’s desire to help and, if necessary, take Koch in ‘on no official basis’, the Germany Emergency Committee received correspondence from the Home Office on February 15th 1939, rejecting the application and stating that ‘we are unable to agree to foreigners, especially foreign doctors, coming to the United Kingdom to settle in employment as laboratory assistants’. Two weeks later, Pool reported to the Retreat Committee that ‘arrangements for admitting Dr. Koch […] had fallen through’.

|

| Letter from M.G. Russell, Home Office (Aliens Dept.) to Miss Nike, Society of Friends' Germany Emergency Committee, concerning Dr. Rudolph Koch, February 1939. |

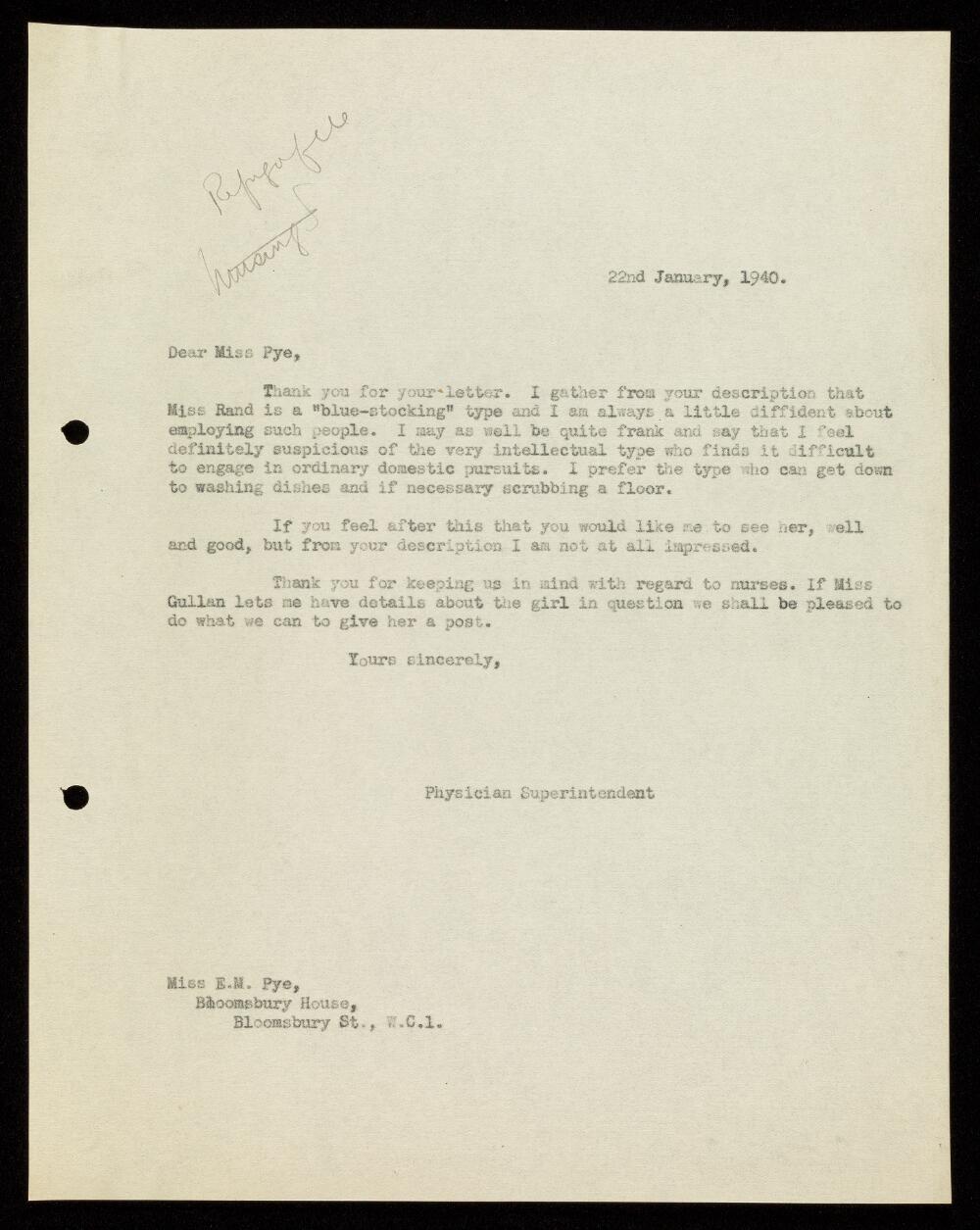

Pool was dismissive of Rand’s appeal. In a letter to the Nursing and Midwifery Department of the Central Office for Refugees dated 22nd January 1940, he described Rand pejoratively as a ‘blue-stocking type’: ‘I feel […] suspicious of the very intellectual type who finds it difficult to engage in ordinary domestic pursuits. I prefer the type who can get down to washing dishes and if necessary scrubbing a floor’. ‘If you feel that you would like me to see her’ Pool concluded, ‘well and good, but from your description, I am not at all impressed’. Rand was forced to look elsewhere for hospitality.

|

| Letter from Dr. Arthur Pool to Miss Pye, Nursing and Midwifery Department of the Central Office for Refugees, concerning Rose Rand, January 1940. |

The following year, a Special Meeting of the German Emergency Committee heard with some perturbation accounts of ‘the amount of mental breakdown among refugees’. In a report in the correspondence file, we read that ‘it is quite clear that there is a growing need for special care for refugees who have not been able to overcome the strains and stresses through which they have lived in recent years’. The report raises concern over the increased risk of attempted suicides, and the need for provision of institutional treatment for European refugees. It is an image much in evidence in the latter half of the correspondence file, which increasingly couples applications for work with appeals for treatment.

While the file largely leaves the fate of its supplicants unresolved, many had either already managed to escape from mainland Europe, or would find safe haven elsewhere in the UK. This was not the case for all, however, and this is no more apparent than in an unanswered letter from December 1938, in which we hear from the brother of Johannes Braun, a ‘very successful actor’. Johannes, ‘tall and broad, good looking’ was prohibited from working in Germany, had retrained as a masseur and, we are assured, ‘could become after some instruction a male nurse’. Dr. Konrad Braun described his brother’s situation as ‘very dangerous and anxious’: a third brother, also a doctor, had already been ‘arrested without any reason but that he is of Jewish extraction’. While ‘Johannes is still free’, Konrad warns us, ‘there is actual danger for his life and existence’.

The Braun family archive, held at the Bodleian Library, reveals that Johannes was arrested by the Gestapo in spring 1942 and taken to the Majdanek concentration camp near Lublin, where he contracted tuberculosis. Within four months, he was dead.

Notes

(1) Letter from Sigmund Freud to Ernest Jones, 23 April 1938. Paskauskas, R. Andrew (ed.). The Complete Correspondence of Sigmund Freud and Ernest Jones, 1908-1939. London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1995, pp. 761-762.

(2) AJR (Association of Jewish Refugees) Information, Volume XLI No. 12; December 1986, p. 7.

(3) Rentetzi, Mari, ‘”I Want to Look Like a Lady, Not Lie a Factory Worker” Rose Rand, a Woman Philosopher of the Vienna Circle’. In Suárez, Mauricio; Dorato, Mauro; and Rédei; Miklós (eds.), EPSA Epistemology and Methodology of Science: Launch of the European Philosophy of Science Association, Dordrecht, Heidelberg, London and New York: Springer, 2010, p.240

Bibliography

Paskauskas, R. Andrew (ed.). The Complete Correspondence of Sigmund Freud and Ernest Jones, 1908-1939. London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1995.

Rentetzi, Mari, ‘”I Want to Look Like a Lady, Not Lie a Factory Worker” Rose Rand, a Woman Philosopher of the Vienna Circle’. In Suárez, Mauricio; Dorato, Mauro; and Rédei; Miklós (eds.), EPSA Epistemology and Methodology of Science: Launch of the European Philosophy of Science Association, Dordrecht, Heidelberg, London and New York: Springer, 2010.

Steiner, Riccardo, ‘It is a New Kind of Diaspora’: Explorations in the Sociopolitical and Cultural Contexts of Psychoanalysis, London and New York: Karnac Books, 2000.