Many researchers into the history of mental health treatment

will already be familiar with the Borthwick’s Retreat Collection, an extensive

archive from York’s Quaker mental health asylum, established in 1796 by Samuel

Tuke.[i]

But the collection should also be helpful to many others, including social,

family and Quaker historians. Of particular interest to this group will be the

Retreat’s incoming correspondence. Following a recent update to the catalogue, summary

information on the 12,000 letters the Retreat received between 1795 and 1852 is

now available online.[ii]

Each letter can also be viewed online at the Wellcome Collection (bundled by

year).[iii]

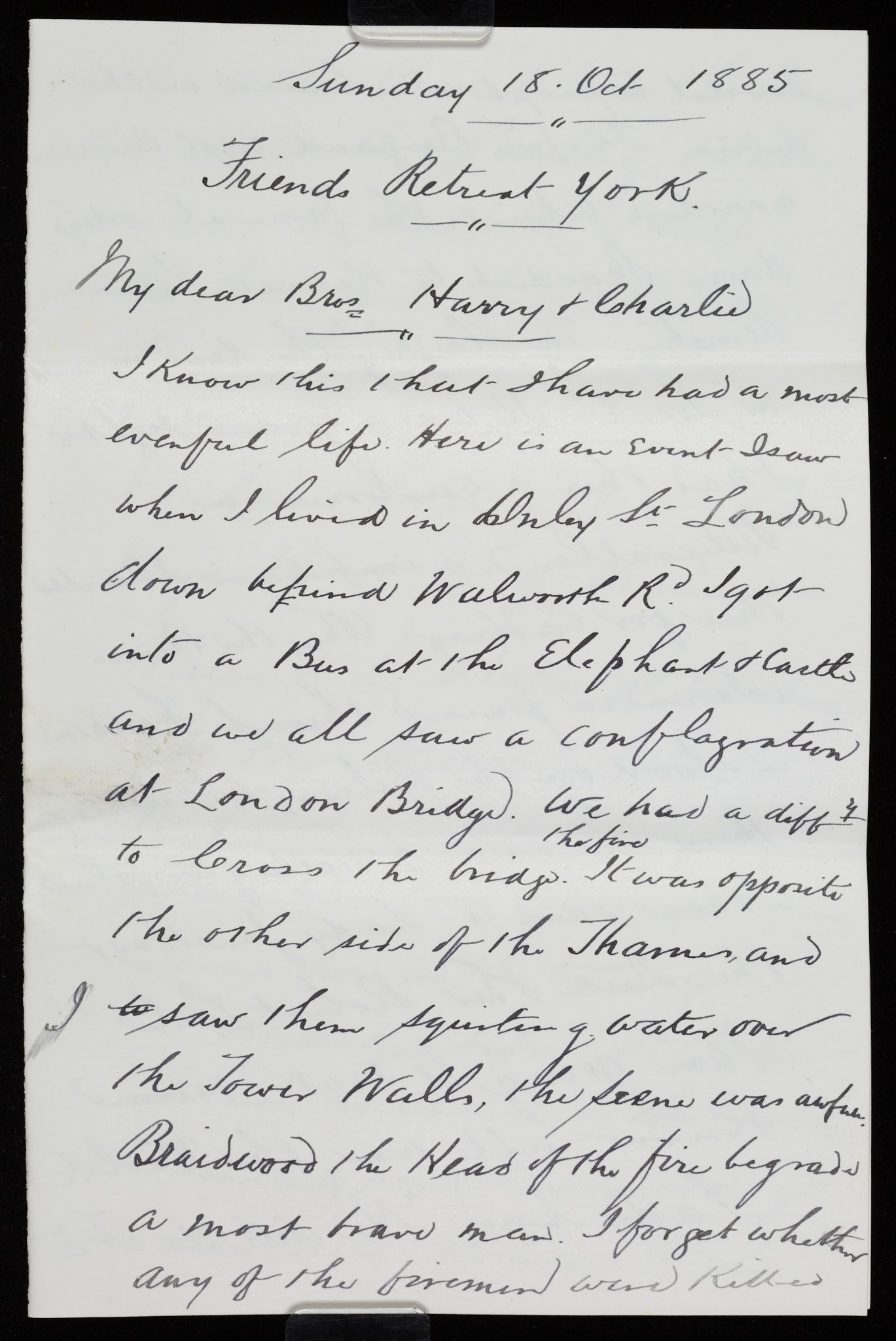

The Proctor family’s story of coping with mental illness in

the family is one of many told in these letters.

An 1826 envelope from the correspondence series

“Stockton 24 / 3mo 1826

Respected Friend,

I duly received thy acceptable

favor this morning and it has indeed afforded us the greatest satisfaction to

find that our dear son appears pretty comfortable and I trust that thro’ divine

favor he will in time be restor’d to us. … … …

Thy Assured Friend,

John Proctor”[iv]

John Proctor was plainly relieved to hear from the Retreat’s

Superintendent that his son, also John, was settled and was optimistic about

his chances of recovery. John Jnr had suffered from a fear of personal injury

since he was twelve. Now, aged twenty-six, things had come to a head. His

phobia was causing him such severe depression that after a particularly severe

attack, his Quaker parents sought help from the Retreat in York.[v],[vi],[vii]

Sadly, despite many years of care and treatment, John never

fully recovered from his mental anguish. Over his adult lifetime, John Jnr was

discharged from the Retreat several times, only to be re-admitted following the

recurrence of his symptoms.

Throughout that time, his family’s support and feelings for

their son are evident in the letters they sent to the Retreat. In fact, the

Proctor family were prolific writers, and their letters chart the highs and

lows of their experience.

Many of the letters are very practical, and his family often

advised the Retreat of parcels of food or clothing they were sending to make

John comfortable. New coats were especially popular! Others share items of news

that may interest him, such as family events or alerting him to their upcoming

visits.

|

| Letter from Jane Thomas to Thomas Allis, 1836 |

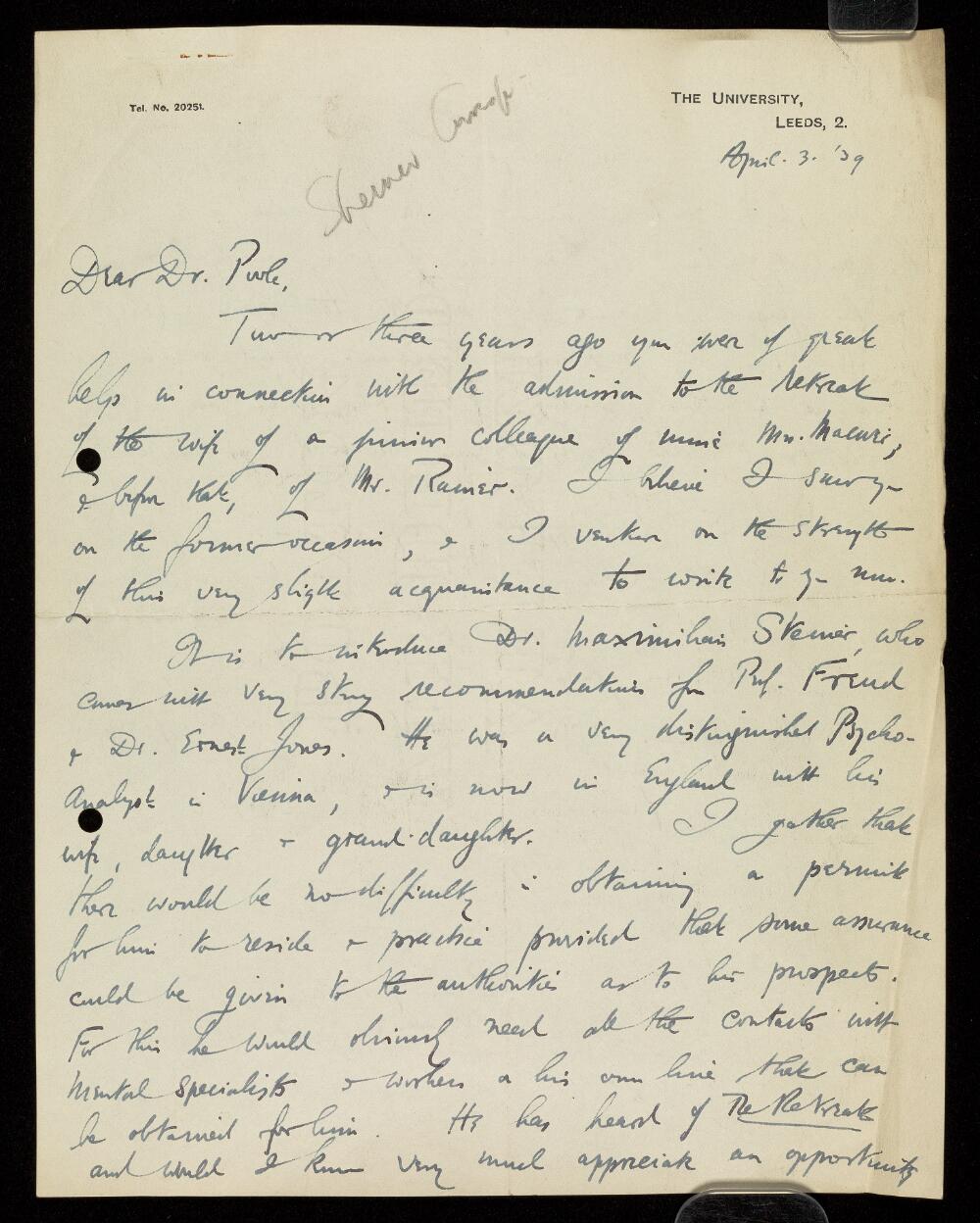

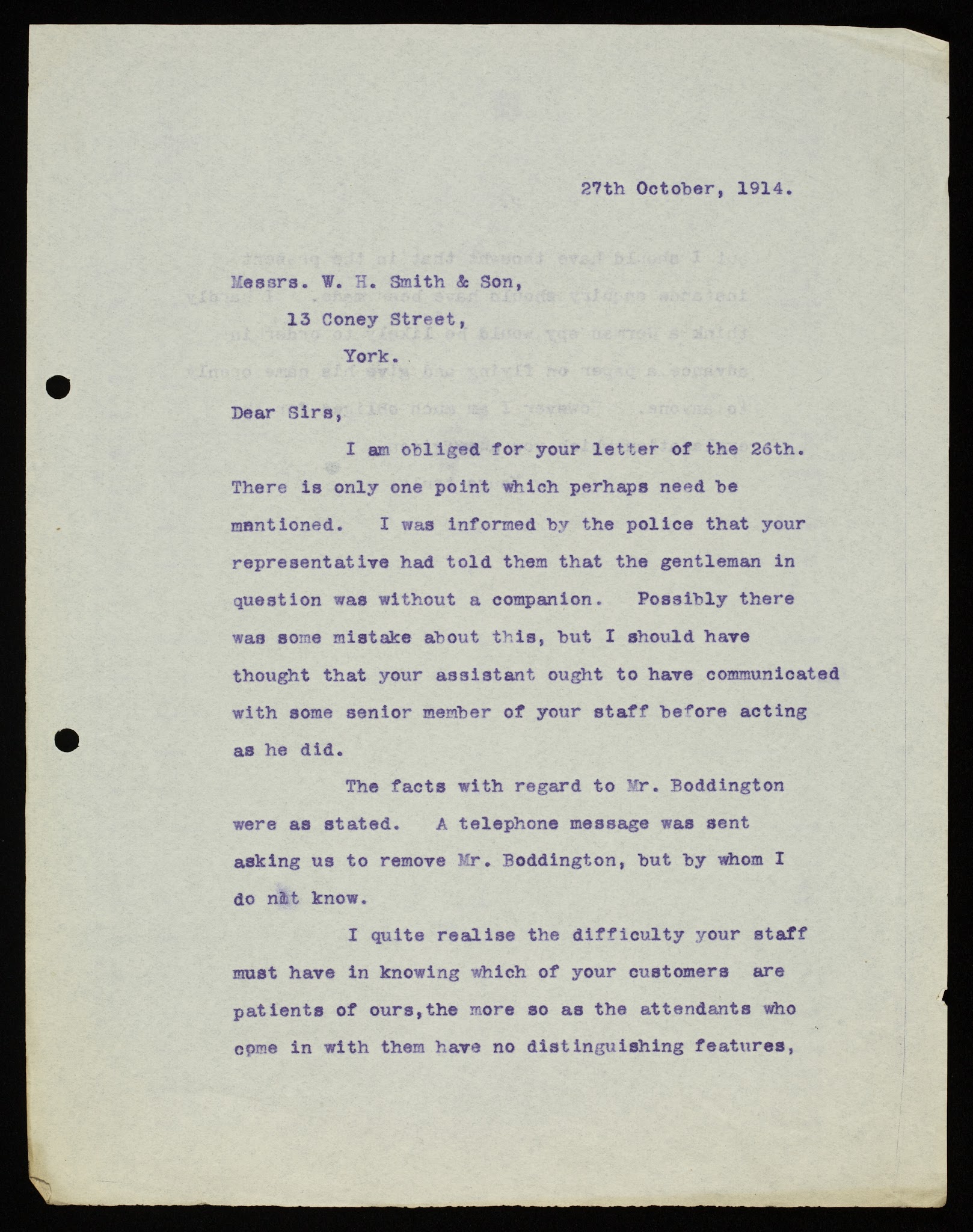

But the letters also reveal tensions. Two years before admission to the Retreat, John had married Jane Spence, and she often disagreed with his parents on his treatment. On one occasion in 1836, Jane was keen to see him return home, where she felt he would be less anxious and have a better chance of recovery.[viii]

His parents, especially his mother, Mary, disagreed with

this, although later said there had been a misunderstanding.[ix],[x]

On another occasion, John Snr was so frank that he ended his letter asking that

it be burnt after perusal.[xi]

Several more bursts of letter-writing can be found lobbying the Retreat regarding

John’s discharge. Such family disagreements were not limited to the Proctors. For

instance, in 1848, Isaac Wright asked that his sister-in-law Elizabeth Wright

be prevented from meeting her husband and removing him from the Retreat.[xii]

Most letters in the Retreat collection use a distinctive

writing style; kind, considerate, humble and supportive. However, the writer

rarely gives you a glimpse of their underlying emotions, making you wonder,

“what are you really thinking?” or “how do you really feel?”

Long-term correspondents like the Proctors occasionally relax their writing style, giving you a glimpse

|

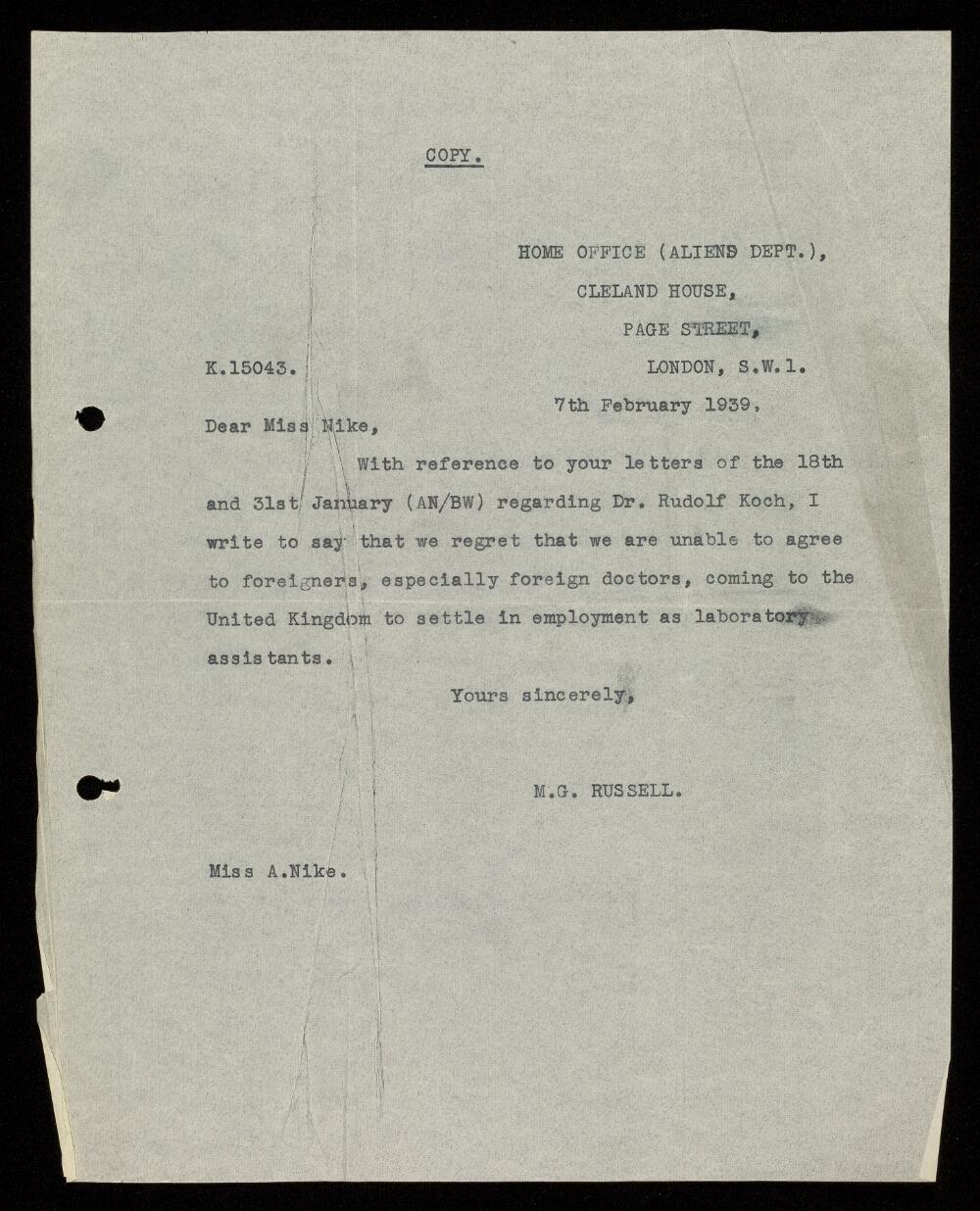

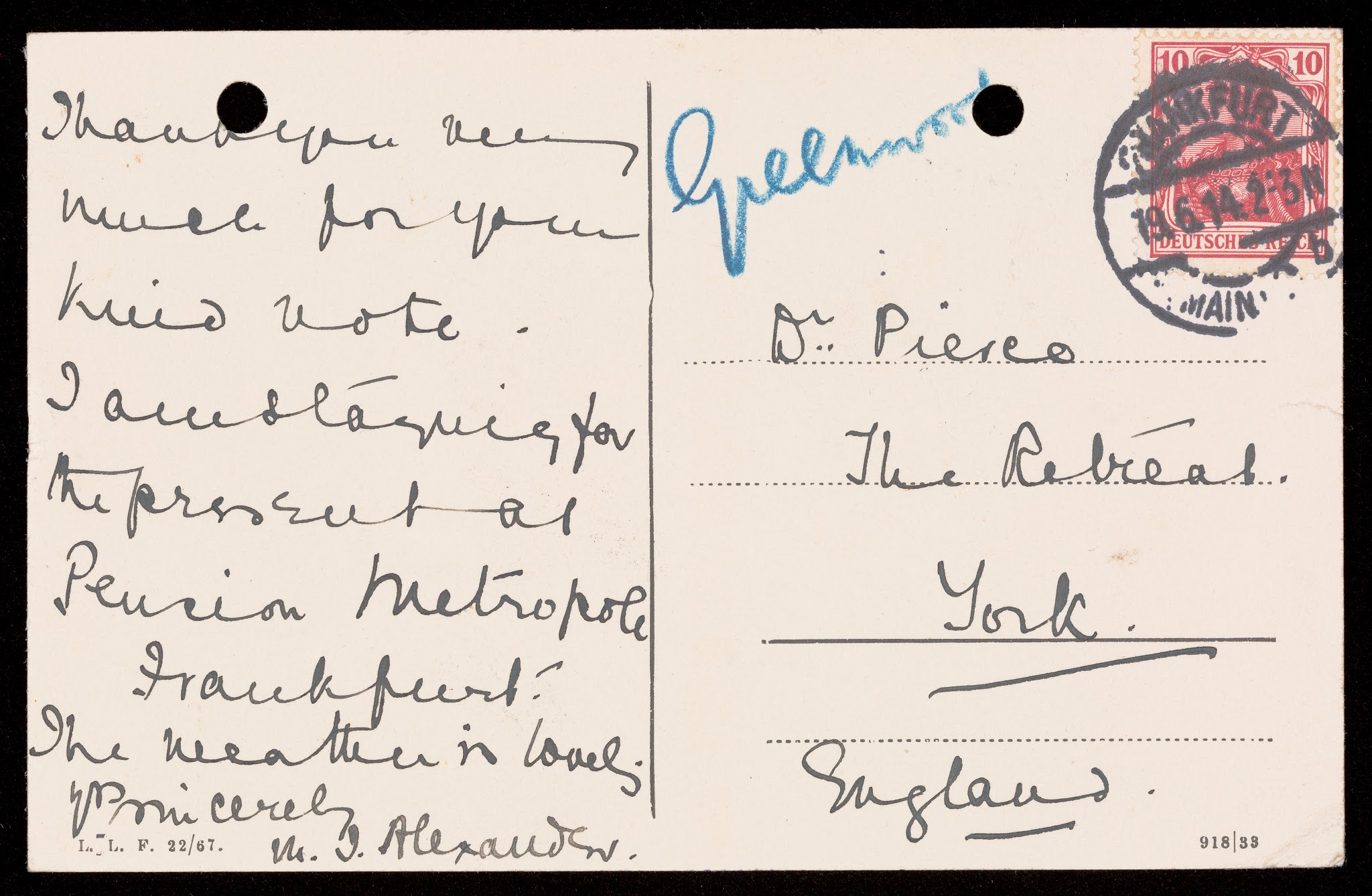

| Letter from John Bright to John Candler, 1845 |

of their underlying feelings. For instance, in her later letters, Jane’s writing strays beyond a ”functional” exchange about clothing and provisions. Instead, you get a deeper insight into her feelings for John and how his absence affects her. In a touching letter addressed to her “dearly beloved Husband”, Jane tries to lift his mood, assuring him, “thou are not forgotten, my love”.[xiii] She talks in poetic terms about the arrival of good weather, recalling his enjoyment of hay-time and how he used to like its “getting up”. “I hardly know what is sweeter than new made hay”, she says. In another letter, Jane is remarkably open with John Candler, the Superintendent at the time.[xiv] She explains that she had been unaware of John’s condition when they married and that “the sympathy of our friends is a mitigation”. However, she now finds herself quite embittered at their fortune and feeling “hardly [unfairly] dealt with in 19 years out of not quite 21, being so bereft”.

John died at the Retreat aged fifty-two, and Jane sent her

final letter in July 1852, ending twenty-six years of correspondence.[xv]

|

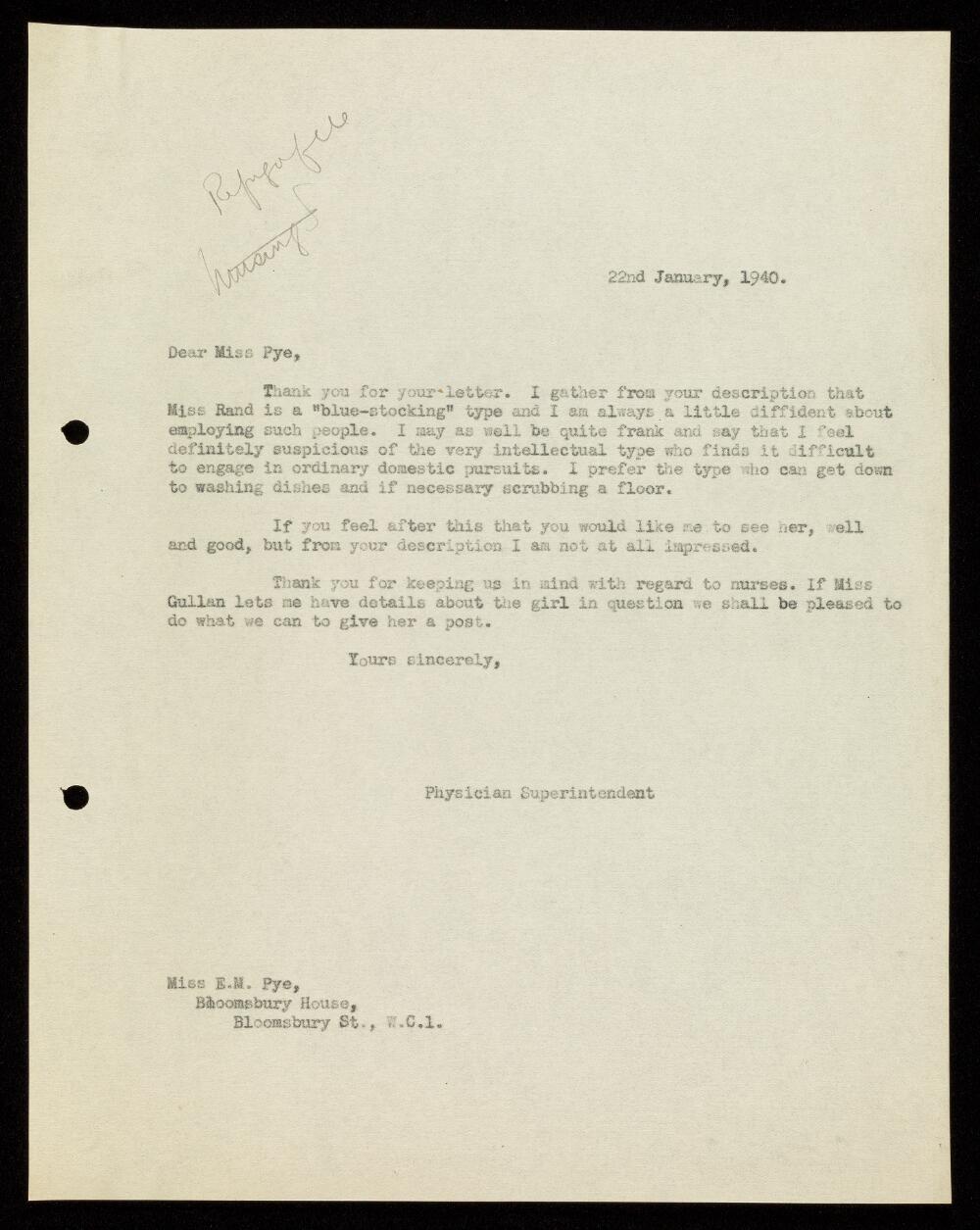

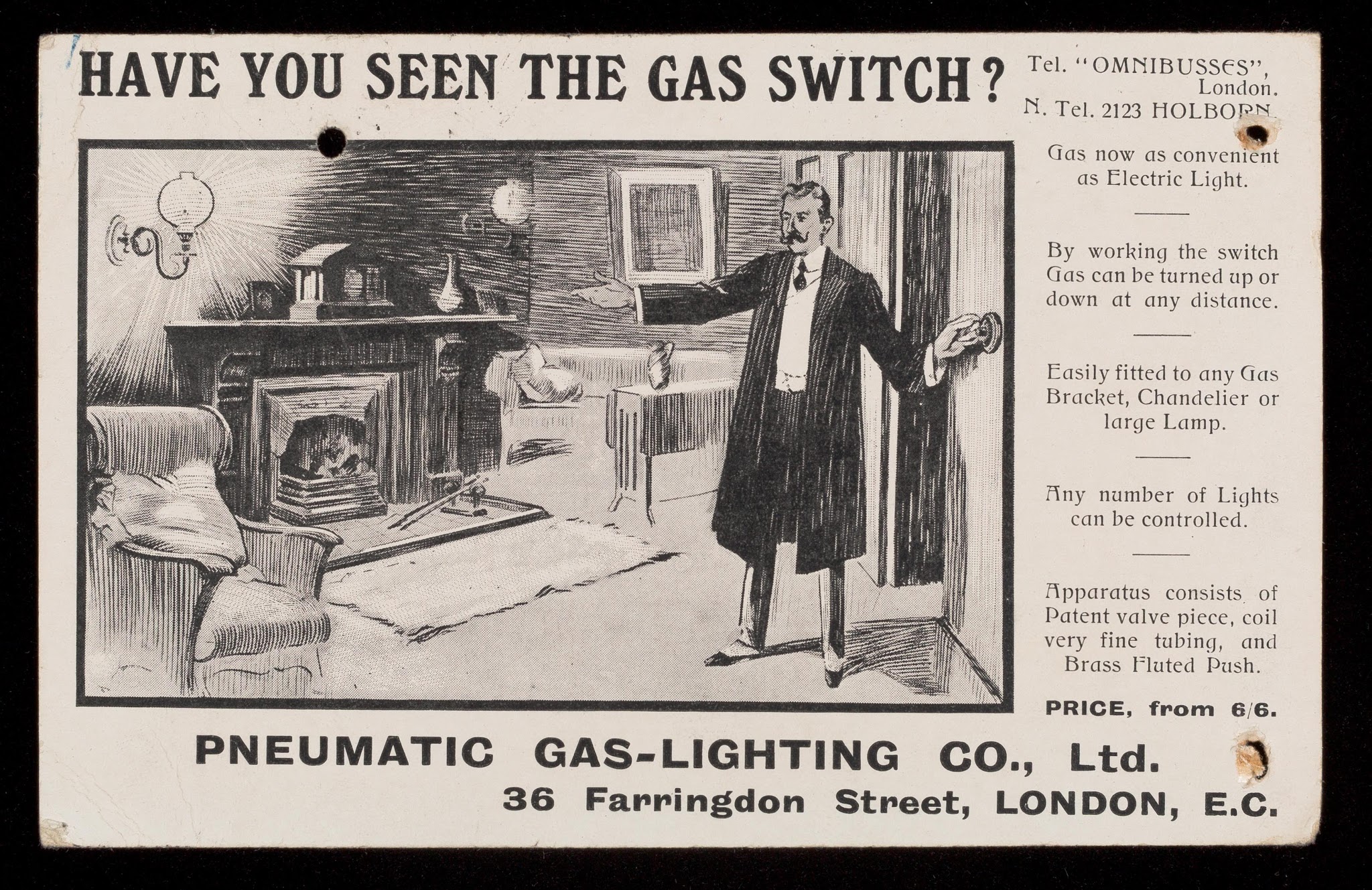

| Letter from Proctor and Son, 1849 |

The archive’s incoming correspondence is a fantastic research resource and is not limited to family letters. For example, there are regular letters from a wide range of Friends’ Meetings across England, sending subscription payments to support the Retreat’s work or paying the accounts of Friends they have placed there. In addition, prominent Quakers often made contact. Sometimes they requested admission for Friends in need or sought advice on setting up and running their own asylums. Occasionally they engaged in discussion about important topics of the day. For example, the 1845 Lunatics Bill prompted a flurry of letters expressing concern that the introduction of new commissioners could interfere with the smooth running of the Retreat.[xvi],[xvii]

The correspondence also gives a flavour of life in the early nineteenth century. For example, visitors

from afar often explained the types and routes of transport they would take, whether road, river, or rail. In addition, the postal options appear to be very efficient, with many letters being received the next day. Some even arrived on the same day!

There are letters relating to running

the Retreat,

such as introductions for potential employees or purchasing goods and

provisions. The records show that the Retreat was a big consumer of cheese. It

received regular deliveries from Proctors of Selby, transported by steam packet

along the Ouse. A typical order could amount to 4cwt of cheese, costing the

equivalent of £1,400 in today’s money.[xviii]

If you’re interested in finding out more about the Borthwick’s Retreat Collection, information can be found at https://www.york.ac.uk/library/collections/named-collections/retreatcollection/

Index of Incoming Correspondence https://borthcat.york.ac.uk/index.php/ret-1-5-1

Images of Incoming Correspondence https://wellcomecollection.org/works/g522gcy8

[i] The

Retreat Collection https://www.york.ac.uk/library/collections/named-collections/retreatcollection/

[ii]

Incoming Correspondence subseries RET/1/5/1 https://borthcat.york.ac.uk/index.php/ret-1-5-1

[iii]

Wellcome Foundation Images https://wellcomecollection.org/works/g522gcy8

[iv]

Incoming Correspondence RET/1/5/1/30 (1826) https://wellcomecollection.org/works/ve2d7urv/items?canvas=102

[v] Admission

Register RET/6/2/1/1 https://wellcomecollection.org/works/en2eated/items?canvas=68

[vi] Admission

Papers RET/6/1/1 https://wellcomecollection.org/works/kvxqcqmq/items?canvas=683

[vii]

Case Book RET/6/5/1/1A https://wellcomecollection.org/works/fe9cszjf/items?canvas=331

[viii]

Incoming Correspondence RET/1/5/1/40/5/22 (1836) https://wellcomecollection.org/works/kqd8cjsv/items?canvas=399

[ix]

Incoming Correspondence RET/1/5/1/40/6/8 (1836) https://wellcomecollection.org/works/kqd8cjsv/items?canvas=472

[x]

Incoming Correspondence RET/1/5/1/40/7/2 (1836) https://wellcomecollection.org/works/kqd8cjsv/items?canvas=588

[xi]

Incoming Correspondence RET/1/5/1/40/5/1 (1836) https://wellcomecollection.org/works/kqd8cjsv/items?canvas=429

[xii]

Incoming Correspondence RET/1/5/1/51/9/14 (1848) https://wellcomecollection.org/works/cxhgsxx2/items?canvas=759

[xiii]

Incoming Correspondence RET/1/5/1/48/7/16 (1845) https://wellcomecollection.org/works/aqsvr7j8/items?canvas=819

[xiv]

Incoming Correspondence RET/1/5/1/48/5/17 (1845) https://wellcomecollection.org/works/aqsvr7j8/items?canvas=637

[xv] Incoming

Correspondence RET/1/5/1/55/8/23 (1852) https://wellcomecollection.org/works/tndc2npc/items?canvas=689

[xvi] Incoming

Correspondence RET/1/5/1/48/7/2 (1845) https://wellcomecollection.org/works/aqsvr7j8/items?canvas=741

[xvii]

Incoming Correspondence RET/1/5/1/48/7/20 (1845) https://wellcomecollection.org/works/aqsvr7j8/items?canvas=767

[xviii]

Incoming Correspondence RET/1/5/1/52/5/11 (1849) https://wellcomecollection.org/works/pqquupp6/items?canvas=343

[xix] Incoming

Correspondence RET/1/5/1/60/6/20 (1857) https://wellcomecollection.org/works/zmzwux7n/items?canvas=543

[xx]

Incoming Correspondence RET/1/5/1/44/2/17 (1840) https://wellcomecollection.org/works/pcu4jg6p/items?canvas=175