By Victoria Taylor

Picture this: the year is 2546, and the University of York as it was in 1966 – and as we know it today, in 2021 – has long since ceased to exist.

Only the ruins of the campus remain, with the lone surviving documentary evidence concerning the University’s origins to be found in the form of contemporaneous press headlines that have somehow survived the ravages of time. Perilously, you work to pull together broken pieces of a narrative, and your conclusions laid out are thus:

|

| UOY/PC/1/13/12, Yorkshire Gazette (October 1966) |

Ironically, and rather meta-textually, I stumbled across this press cutting from the Yorkshire Gazette discussing how headlines might be used to help piece together history during my very own foray into press cuttings concerning the origins and early history of the University of York which I have been undertaking as part of my Public History MA placement at the Borthwick. Thankfully, the archive that I was working with contained both articles and headlines, allowing me to discover slightly more about the early days of York!

Whilst some of 1960s humour might be lost on us today, the satirical sketch – which was performed by some of York’s staff and students as part of an historical exercise after the appointment of York’s very first honorary doctorates in 1966 – highlights the importance and limits of archival holdings, and one way in which a specific kind of archive – namely press cuttings – might be used to help us understand and remember the past, distant or not.

Although excavation of York’s hypothetical ruins would reveal a certain amount of information relating to buildings’ dating and development, only so much would be able to be garnered about the people – and ideas – behind them. For this information, it is into the archives that we must – as the brave researchers of 2546 will do in the future – head. For it is in archives that we find stories from the past.

* * * * * *

York’s early years: stories from the press cuttings

The prospect of a university in York was a hot topic from the late 1940s onwards; consequently, there are thousands of cuttings detailing various aspects regarding the development of the University. From the early days of the

summer schools, when the hope of a University was nothing but a distant glimmer on the horizon, to the graduation of the very first cohort in 1966, the press reported on a multitude of subjects. It would be impossible to adequately summarise the vast scope of the holdings, but I will take a moment to highlight the versatility of the contents by picking out some of my favourite cuttings and the stories they reveal.

The enduring popularity of family history

Today, if one wishes to research their family then they can

hop onto one of the many ancestry sites that have popped up over the

recent years and trawl over a variety of records (from archives!) that have

been digitised or request them through the post. In the past, the onus was on

archival institutions to deal with such requests for genealogical information,

and the Borthwick Institute – officially opened at St Anthony’s Hall in 1953 –

was one such institution that was inundated with requests.

|

UOY/PC/1/13/30, UOY/PC/1/2/58: Northern Echo (June 1966),

Yorkshire Post, Northern Guardian (November 1953) |

Several cuttings in the archive are concerned with genealogical requests at the Borthwick, which – indicative of the 60s' opinion that family history was a less worthy historical research pursuit – apparently impeded the ‘proper’ historical research being undertaken at the Borthwick due to the sheer number of them. Requests came from far and wide, including America, and led to, quite possibly, my favourite piece of wordplay throughout the entire archive:

“…it may not be possible to see the historical wood for family trees.”

A diverse student population

|

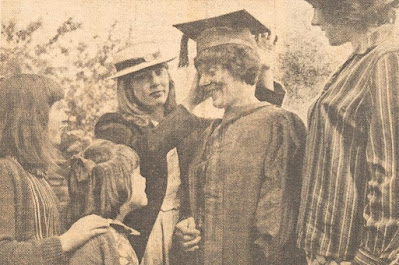

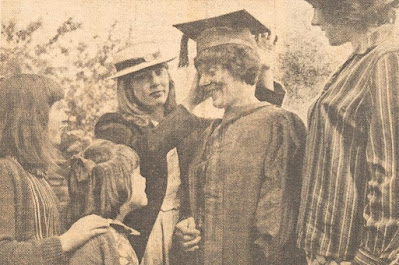

| UOY/PC/1/7/103, Northern Echo (October 1963) |

If you were asked to guess at the relationship between the man and women in the adjacent picture, with the only context given that it depicted people linked to the University of York, a variety of conclusions could be reached. The most obvious answer, perhaps, would suggest that this was a lecturer talking to students. This explanation would certainly fit comfortably with traditional perceptions of what academics and students looked like. However, this was not the case. Every person in the photograph is a student: indeed, this is a group of students from the very first undergraduate cohort to pass through the gates of Heslington Hall in 1963.

George Crofts – pictured seated – was 64 years old when he enrolled at the University of York to study Economics: he was, unsurprisingly, the oldest undergraduate. A World War I veteran and a pharmaceutical chemist, Crofts – following his retirement – moved from Newcastle to York to take up his place at the University and was successfully awarded his degree in Economics with Economic and Social History in 1966.

Crofts was not the only mature student to enrol in 1963. Mary, a mother of four from the City of York, joined in her thirties to study Economic and Politics because she saw no reason for women her age being confined to making tea or knitting. Like Crofts, she was one of the first graduates of the University and set a fine example to her daughters. Anyone, seemingly, was welcome to study at York provided they had the qualifications: there was no conventional image of a ‘York student’ to be upheld.

|

| UOY/PC/1/13/37, Yorkshire Evening Press (July 1966) |

Not only were mature students welcome, but so, too, were overseas students. Even in the earliest days of the Architecture and Archival summer schools, there had been a focus on establishing York as an internationally renowned place of study. In 1953, York was one of various cities cooperating with the British Council to host a yearly course in the spring entitled ‘Life in an Historic City’, which offered overseas students studying in UK universities the chance to experience the machinations of local government and life in British cities: a course which ran regularly in the following years. International students were commonplace in York, and it is unsurprising that there was talk of York becoming a ‘School of Britain’ at one point when it seemed as if the university dream was dead in the water.

|

| UOY/PC/1/1/24, 160, Northern Echo (August 1949), Yorkshire Gazette (August 1952). |

(L) Michael Onafowokan of Nigeria, studying architecture at Glasgow University, undertakes measured drawing at York Castle in 1949 as part of a York Summer School on architecture. (R) Students from the UK, Malaysia and Sudan sketching and measuring features at the Treasurer's House, 1952.

|

| UOY/PC/1/3/66, Yorkshire Evening Press (April 1966). |

The first cohort of students in 1963 was not lacking in international students but, unsurprisingly, they were in the minority. Students arrived in York from India, Kenya, the USA, Nigeria, Hong Kong, Iraq, Sudan, France, and Germany, to name but some of the countries. A name that may be known to those already familiar with the University’s early history might be

Pradip Nayak, a student from Kenya studying Economics and Politics, who was elected the first president of the Students’ Representative Council in 1964. Nayak was actively involved in student politics, with the Yorkshire Post describing him as “a leading light of the student movement”.

Following its official establishment, it did not take long for York to actively seek to develop its international links. In 1964, links were established with, what was then Northern Rhodesia, Zambia; in the 1964/1965 academic year, York – in association with the Ariel Foundation – hosted several African students studying Economics. The Zambian contingents of this group even celebrated their country’s independence at King’s Manor a day early so that they could travel to London the following day to take part in official celebrations.

|

| UOY/PC/1/9/99, Yorkshire Post (23 October 1964) |

Student activism

Universities in the 1960s were well-renowned for their student activism, and, despite York’s climate being tamer than some of the more radical establishments, York students proved to be just as committed to their causes.

In 1964, for example, students from the University of York and St John’s College joined together to protest the life sentences that had been handed down to South African anti-apartheid activists by holding an all-night vigil in King’s Square.

|

| UOY/PC/1/9/21, Yorkshire Evening Press (June 1964) |

York students also took to the streets in the winter of 1965 to condemn Rhodesia’s Universal Declaration of Independence (much to the chagrin of some York residents who were out to see Father Christmas).

|

| UOY/PC/1/11/155, [unattributed cutting] (November 1965). |

The Vietnam War was also a point of focus throughout the

early years: in 1965 York’s Debate Society passed a motion condemning American

aggression in Vietnam demonstrations were planned, and signatures were

collected for a petition to be sent to the Prime Minister that urged the

government to encourage a peaceful resolution to the conflict. In 1966, some

York students got into hot water with the British Legion for giving out white

poppies for others to wear on Armistice Day in recognition of the impact of the

Vietnam War.

Indeed, so fed up with the image of the protesting student

in mid-1965, two York students protested the protests that had been taking

place, positing contrary opinions on several subjects that had other University

of York students up in arms!

It was not all protests,

however. Students were often behind fundraising attempts. The York

University Movement for Racial Equality worked in tandem with Keighley

International Friendship Council in 1965 – as well as the Linguistics and

Education departments at York – to help teach English to immigrants in

Keighley. The Movement launched an appeal – which was successful – for £1,000

that was to pay for the upkeep of a rented social centre that would enable the

scheme to develop.

|

| UOY/PC/1/11/150, Telegraph and Argus (November 1965) |

'Sporting’ endeavours

Forget the annual ‘Wars of the Roses’ competition with Lancaster University: the hottest sporting action to be found in the archives concerns the University of Hull’s challenge of a Winnie the Pooh contest in 1966. Posted on University of York’s noticeboards, Hull students challenged York students to a game of Poohsticks and Pooh hums – for those uninitiated, Poohsticks is a game that involves two sticks, a body of flowing water, and a bridge (what better campus than York’s for such a competition with its largest plastic-bottomed lake in Europe and bridges, one might ask; one with faster running water, one might answer), and Pooh hums were to be songs that would be judged on their “Poohishness”.

Sadly, I could find no articles discussing whether any courageous York students took up this most daring of challenges – should the University of Hull, or any students of the time, be able to clarify any information, I would gladly welcome it. [1]

* * * * * *

Limitations and lacunae: memory and forgetting in the archives

Whilst there are many and myriad benefits from examining the archive to gain an understanding of the University of York’s early history, it is also necessary to recognise the archive’s limitations. The 1966 sketch acknowledged that, in the distant future of 2546, there would be no evidence of the sketch having taken place, and this observation highlights the fact that archives, no matter how varied their contents, cannot record everything, which can have a significant impact on what and who is remembered.

The art of selection

In fact, archives contain only brief slivers of a vast, expansive past. For the researchers of the future to be aware that the sketch had taken place, an account of the sketch would have to have been documented in a newspaper headline. This would require: a journalist to decide the moment was worth documenting in the first instance; the volume’s compiler to decide that the cutting was worth including; an archivist to decide to keep the volume in an archive; a useful finding aid to be created to search through the surviving cuttings; and it would require this archive to be cared for to survive into the future (whether this survival would be in paper or digital form is a question for another day). For survival, selection is imperative at every point.

Selection highlights just how easy it is for an event, a person, a group of people, to be consigned to the cutting-room floor: to be forgotten even in the quest for memory. The necessity of selection has, in the past, created lacunae in archives, and it is frequently the least powerful in society that suffer from this lack of documentation and lack of representation in the archives. Thankfully, action has been taken – is being taken – to redress this wrong: whether in state archives, or in more local, community archives, efforts are underway to preserve the histories of the most marginalised groups on their own terms.

Selection at work in the press cuttings archive

In terms of where selection fits into the archive that I have been working with, it is not necessarily a case of archival selection that delimits the contents – in fact, the collection process seems to have been rather indiscriminate, with the only criteria necessitating that articles must mention the University in some capacity – but rather the nature of the archive itself. It is an archive of press cuttings and press cuttings alone, which ultimately means that its contents reflect the interests of the press throughout the 1950s and 1960s.

Stories included in the press cuttings can vary from the mundane to the scandalous, but there is little doubt that they do not – indeed could not – report on every minute happening concerning the University. Selectivity at work once again. Moreover, the articles often tease at information that they cannot further elucidate on. A case in point: a 1966 Yorkshire Evening Press article discussed an Eboracum article written by a first-year student concerned with the relationship between overseas and home students and the existence of unofficial segregation. The cutting acknowledges the existence of this tension but does nothing more to explore the matter: there are no interviews with international students documenting their experience at the time, for example.

|

| UOY/PC/1/12/89, Yorkshire Evening Press (March 1966) |

Combating selectivity

How do archives avoid complacency and recognise the gaps in the historical record? I already mentioned the efforts that have been taken elsewhere in archives to combat the impact that such selectivity can have, and similar principles might be applied here. The early years of the University of York’s history are still within living memory, and this means that steps can be taken to counter archival gaps, helping to guarantee that the archival record will be more inclusive and representative of everyone involved in the University of York’s history.

In other words, let us hope that the exploration of a press cuttings archive can be used to start conversations about the early years of the University of York as opposed to finishing them, creating a comprehensive and inclusive archive that might survive into 2546 and even beyond.

[1] Do you know if York accepted the challenge? Do you have a photographic record of the events or an original 1966 Hum or rhyme? If so, please contact the Borthwick and let us know!

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.