Scotch cloth, for example, was a fabric said to resemble ‘lawn’ (a plain weave textile of linen or, latterly, cotton) but cheaper - it was sometimes said to have been made with the fibre of nettles.

And what better to wear with your scotch cloth shirt than a scotch cap? In his will of 1551, Thomas Greenwood of Wakefield stated:

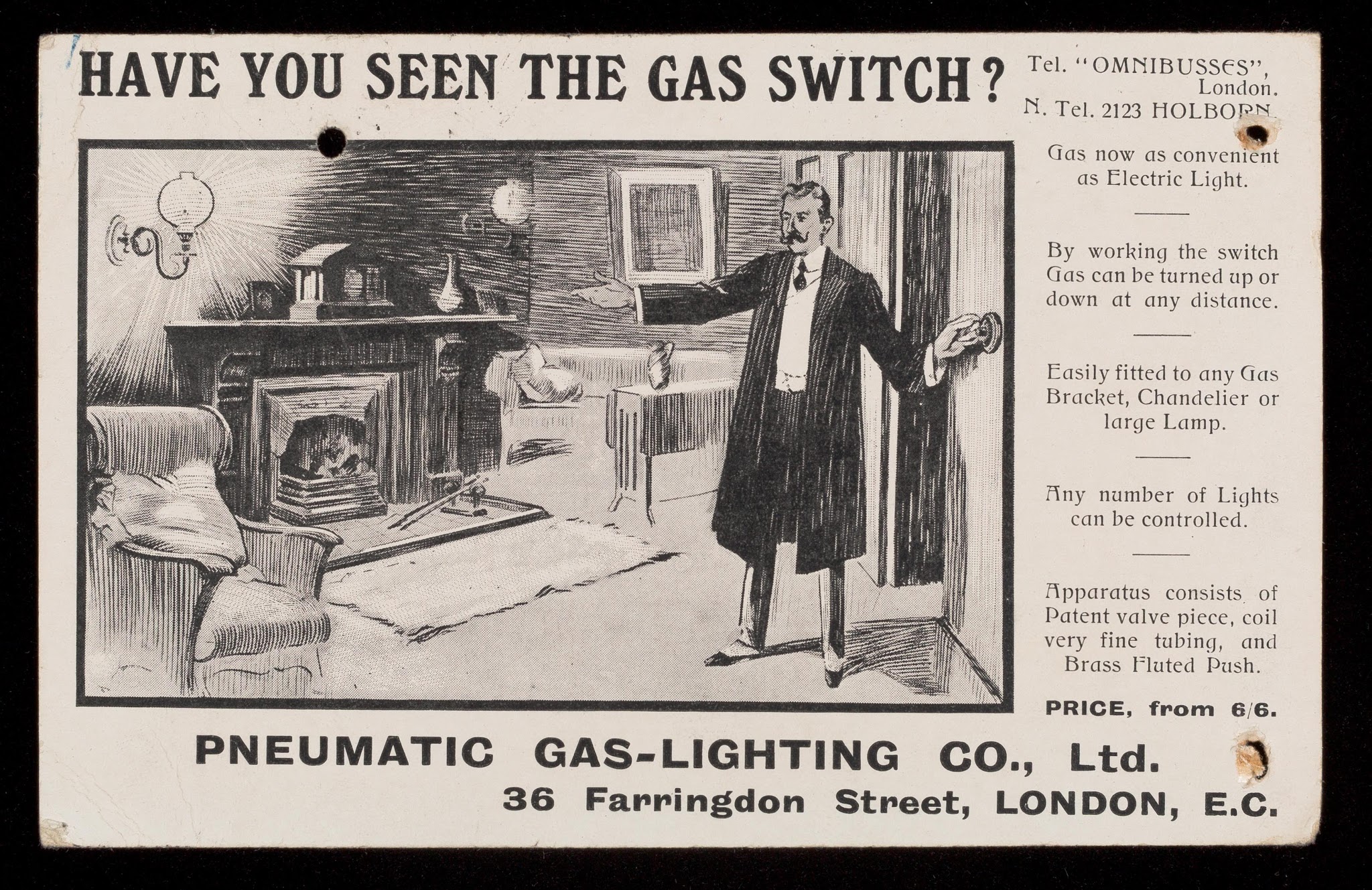

Unto Edwarde Sundderland as it apperethe in my booke of parcels for a remnantte of calve skynes so that the said Edward do allowe to me xxs which I paid for hym to William Parkyns, besides a Scotche cappe that he had of me, and I owe unto hym for whitte carsayeThis was not a scotch bonnet or a tam o’shanter but something more like a Glengarry cap or Balmoral bonnet. The OED has examples from 1591 and describes it as ‘a man’s head-dress made of thick firm woolen cloth, without a brim, and decorated with two tails or streamers.’ Something similar is now worn by Scottish military regiments:

|

| A Balmoral Bonnet, similar to a scotch cap |

- Alexander Miller… and another Scotchman taken up with a pack on his back (1705, Gisburn)

- Mary Hanson had bought the musling of one Robert Maxfield a Scotchman (1721)

- One piece of red and white printed linen which she saith she exchanged with a Scotch Man for her son’s hair in 1736 (1738, West Riding)

Saith that he was borne in Scotland and Dumfrees and he came into England the fooreende of May last and sells hollan and scotchcloath, cambrick, muslins, callecoe and blew linne and that he came Almondbury to Kirkheaton and there was taken up by the watch and hath used this pedding traide for five yeares last paste in England and that he byes the comodityes, except the scotchcloath, of Mr Hardwick and Mr Hey both of Leeds

|

| 'A Scotchman borne att Edenborough Cominge out of the South dyd as he was brought from Borrowbridge and was buryed att Kirby' Oct 25 1666 N/PR/KM/1/1 North Yorkshire County Record Office |

By 1881, Joe Whiteley of Lancaster Street in Barnsley was referring to himself as a ‘Scotch Traveller Drapery’. His West Riding surname, combined with his birthplace of Holmfirth, suggests that by this date, scotchman had become a more generalised term for a travelling salesman:

Scotchmen generally dealt in cloth, so they probably weren’t carrying pounds of nails on their backs. In addition, the existence of the word scotsemnail in Yorkshire from the medieval period seems to predate the arrival of the scotchman by several hundred years. The word is found frequently in the county from the early fourteenth century and seems to derive itself from a Scots dialect term: a seam was a nail, especially one which fixed together the planks of a clinker-built boat. The suffix ‘-nail’ may have been added by clerks who were unfamiliar with the regional word - probably the Yorkshiremen who bought and used them just referred to them as scotsem.

References to scotsemnails occur in the York area from the fourteenth century:

1371 Et in 10.m de Scotsomnail emptis pro celura, dando pro c. 5d, 41s 8d

1434 In v. m Scotesemnailes, 5s 5d

1518 Item paid for ij M skotsym, ijs

1535 It’m twoo thowsand skott Semes (Stillingfleet)

1537 scotsem nayles otherwise called lathe nayles (Sheriff Hutton)

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Scotch cloth: A textile fabric which resembled 'lawn' but was cheaper.

Scotch cap: A man's head-dress made of thick firm woollen cloth, without a brim, and decorated with two tails or streamers.

Scotsemnail: A 'scottish nail', one that could be clenched.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Alexandra Medcalf

Project Archivist, Yorkshire Historic Dictionary (@YorksDictionary)

Edit 25/01/2019 The Yorkshire Historical Dictionary is now available online at yorkshiredictionary.york.ac.uk

Edit 25/01/2019 The Yorkshire Historical Dictionary is now available online at yorkshiredictionary.york.ac.uk