As the

Archbishops’ Registers Revealed project is drawing to a close along with the

year 2015, I wanted to offer a brief overview of my involvement in the project.

It can be quite tricky for a conservator to accurately convey exactly what it

is they do in the workshop. This blog certainly isn’t as catchy as the 12 Days

of Christmas - but I hope that it provides some advent calendar-sized tasters of

the work I have been doing.

|

| 12 Limp parchment volumes |

There are some things that conservators can do to improve the digitisation process – cleaning, unfolding, repairing, etc – but there are also some things that we cannot improve. We can clean a surface, which will lighten the areas around the ink and make the ink stand out better, but we cannot replace abraded or faded ink. Consequently we do need to assess archives before a digitisation work plan is put in place, so that we know what we will need to tackle and how long it might take.

Abp Reg 11 is the volume that required the greatest number of treatments.

|

| Abp Reg 11 with the highest number of treatments recorded |

Within the 37 volumes that were treated but not disbound 610 treatments were documented in total. 127 of these treatments were undertaken within Abp Reg 11. Treatments ranged from dry cleaning the surface of folios or unfolding the corners of a folio, to removing a previous repair that was obscuring text or repairing the edge of a folio that had suffered loss and damage. We would only undertake treatment where either text had been obscured (by dirt or folds) or the area was vulnerable to further deterioration during handling. Without this guideline in place it would not have been possible to complete the treatments in time for the digitisation to take place!

10 volumes required paper repairs.

|

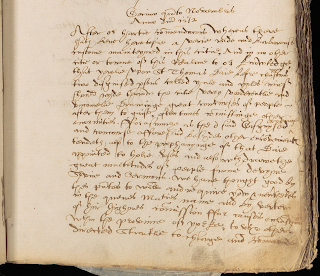

| 10 volumes contained paper in need of treatment

such as this document

|

10 volumes required paper repairs.

|

The majority of the folios in the Archbishops’ Registers are parchment, but there are occasional paper inserts and modern paper endleaves in the volumes too. 33 of the 610 treatments mentioned above were on paper, but almost all of the others were on parchment.

9 descriptive phrases for the metadata that created plenty of

debate. |

This is a

very subjective number, which would certainly fluctuate depending on who you

spoke to! I first became involved with the metadata when it became apparent

that not all of the images could take their image number from a folio number.

The Archbishops’ Registers are nothing if not inconsistent, and there were

various hiccoughs to accommodate, as well as the structural features of each

volume (and those thrown in from previous bindings). A lot of my time was spent

deciding what information to include, what to leave out, and which terms best

reflected what the end user would see in the image.

|

8 volumes requiring only minor treatments such as

the dry cleaning shown here

|

8 volumes requiring minor work…

|

|

As opposed to 32 volumes requiring major work! In my initial

assessments, ‘minor work’ refers to cleaning or small areas of flattening.

‘Major work’ includes larger areas to flatten and more invasive or time

consuming treatments. A small local humidification with a non-aqueous solvent

could be applied and dried within an hour or so, whereas the application of a

repair would take a minimum of 3 days of treatment when drying time is taken

into account. My workflow planning needed to take all of this information into

account, so that I could ensure the photographer had a seamless flow of volumes

to image and process.

The Archbishops’ Registers vary in size, but the most

memorable

volumes are the largest. 7 of the volumes have spines between 10 and 15cm wide.

Several of these have also been bound with thick wooden boards, and

consequently they are large, heavy and unwieldy to manoeuvre. This has made

them challenging to handle safely during conservation and digitisation. In

spite of this (or partly because of this?) these are some of my favourite

Registers – most of the bindings still function well, and they have an

undeniably weighty presence. I can’t help but think when I look at them that

they must contain a formidable number of sheep!

|

| 7 spines over 10cm in width |

6 hours of Conservation at the Summer

Institute.

| |

|

5 sheets of goldbeater’s skin

|

5 sheets of goldbeater’s skin used

to repair damaged parchment such as the example above from Abp Reg 10 f.25

(left: before treatment; right: after treatment) |

4.3 kg of magnetic restraint

|

| 4.3kg my favourite magnetic pull strength |

I have been using magnets as a tool to restrain parchment

when it is drying. I use a ferrosheet under the parchment folio, so that a

magnet placed on top of the parchment will hold the parchment in place. I have

experimented with various sizes and strengths of magnet, but my current

favourite is a neodymium cylindrical magnet of 12mm diameter and 6mm height at

a strength of N42 which gives a pull of 4.3kg!

3 volumes disbound

The decision

to disbind any of the registers was not taken lightly. The process is very

invasive and can risk damaging the register; loose leaves are more vulnerable

to future deterioration than those in a binding; removing the binding alters

the format of the register; and historical evidence can be lost during

disbinding. On the other hand the bindings we were considering were not

original bindings; they were very stiff, which obscured a significant

proportion of text on the majority of folios; and the stiffness of the binding was

also hindering the functionality of the volume. 3 registers have been disbound

and digitised as loose leaves. A major concern for the New Year will be to

discuss with the archivists whether these registers will be re-bound, and if so

in what manner.

|

| 3 registers disbound |

|

2 sheets of gelatine remaining, used

for repairs

and poultices such as the example above

|

2 sheets of gelatine remaining

I have been

using gelatine as my main adhesive of choice for both paper and parchment

repairs. I have also used gelatine to create poultices, which I have used for a

number of treatments. Poultices allow a slow transfer of moisture. I have used

them to soften the adhesive of previous repairs in order to remove them. I have

also used poultices to remove paper guards from parchment inserts. Lastly, I

have been using gelatine poultices to remove materials that have been adhered

to the spines of the volumes I have disbound. Including the volumes that have

been disbound, I have used poultices to treat 289 folios, and removed spine

linings from 3 volumes. This has used 61 sheets of gelatine – with 2 sheets

left over for the New Year.

|

1 happy conservator!

|

1 frazzled but very happy conservator

I have

sincerely enjoyed working on this project. It has been a privilege to work on

the Archbishop’s Registers, and a pleasure to work with such beautiful volumes.

I look forward to seeing the images of all the registers available online in

the not too distant future!

Catherine Dand, Project Conservator