By John-Francis Goodacre, Archives Trainee

Imagine stepping into a house. Nobody is at home, but a row of books lines the bookshelf. How much can you tell about the person who lives there?

This is the situation we can find ourselves in when reading probate inventories, the lists of movable goods that were drawn up after a person’s death in order to assess their wealth and calculate church court fees. These lists can offer an incredibly rich insight into the everyday lives of people long dead, through a snapshot of what they owned at the time of their death. Though many inventories only record clothing, household furniture and livestock, some occasionally contain detailed evidence of book ownership. One such inventory in the Borthwick’s Yorkshire Probate Records tells the story of an avid reader in seventeenth-century York.

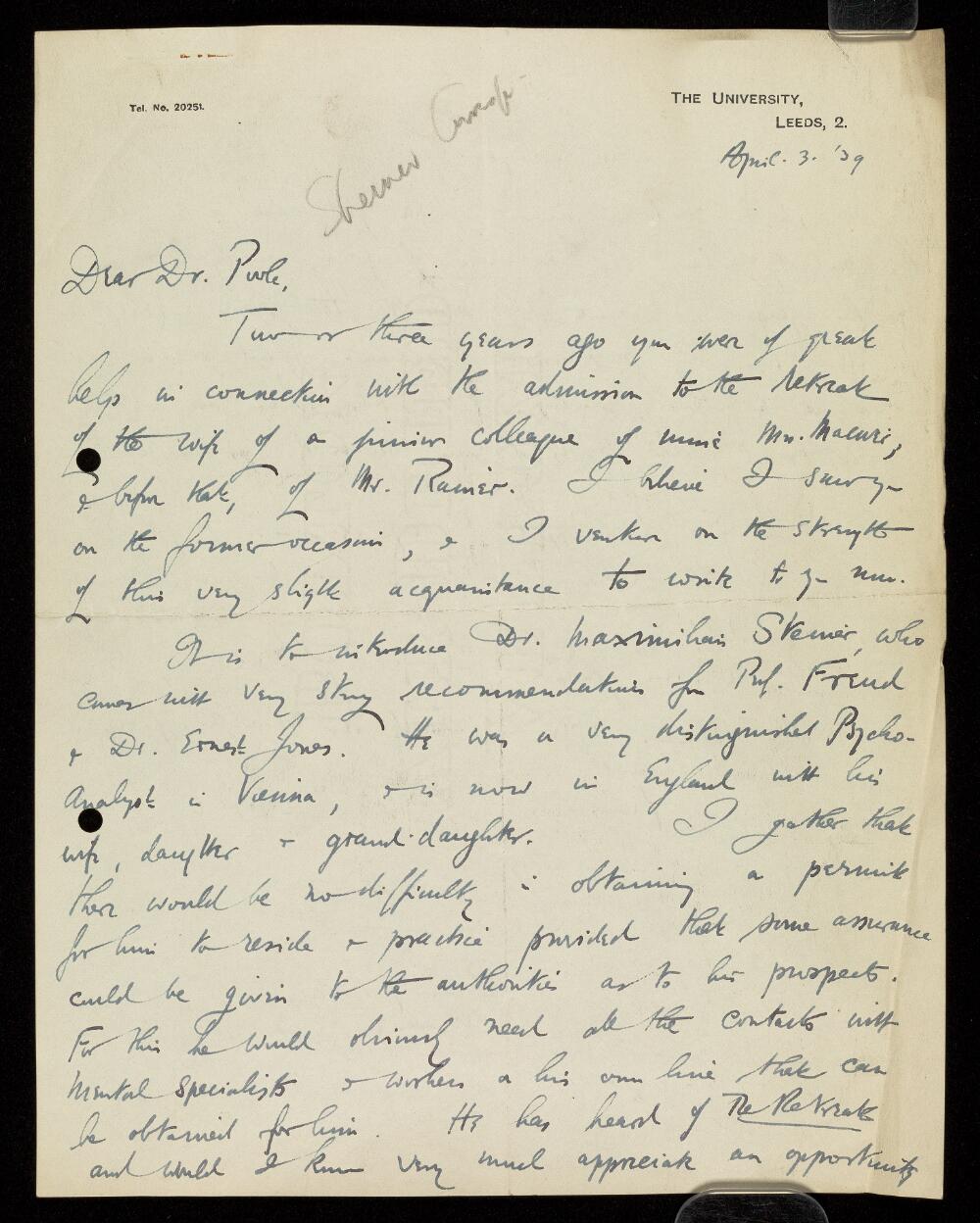

Isaac Havelock died some time before September 1640. His estate passed through the Prerogative Court of York, and four men were instructed to make an inventory of his goods, which they did on the 31st of August. This inventory - a long piece of parchment written on both sides - records an impressive array of furniture in York, as well as a large selection of goods in Berwick upon Tweed, including fine clothes, five gold rings, a silver watch and chain, and a horse. What makes the document stand out, however, is the category of items that is given its own space in the end, making up a good third of the entire inventory and over a quarter of its value. The “Schedule of his books” records at least 132 books, of which 43 are individually named.

The beginning of Isaac Havelock’s inventory.

There is little else we know about him. The other documents that one would expect to find in a probate bundle - a will, a grant of administration, a bond - haven’t survived, so it is not clear what his occupation was or to whom he left his possessions. There seem to have been Havelocks living in the villages of Skelton-in-Cleveland, Marske and Guisborough in the North Riding of Yorkshire, and the parish register of Skelton records the baptism of an Isaac Havelock, son of John, on September 28th 1587. Isaac Havelock also appears as a witness in a number of deeds from the area around York between the 1610s and the 1630s, including one where he is described as a servant to Richard Bell Esq., a counsellor-at-law of York. Of all the archival sources, it is thus the list of books which gives us the most detailed insight into his life.

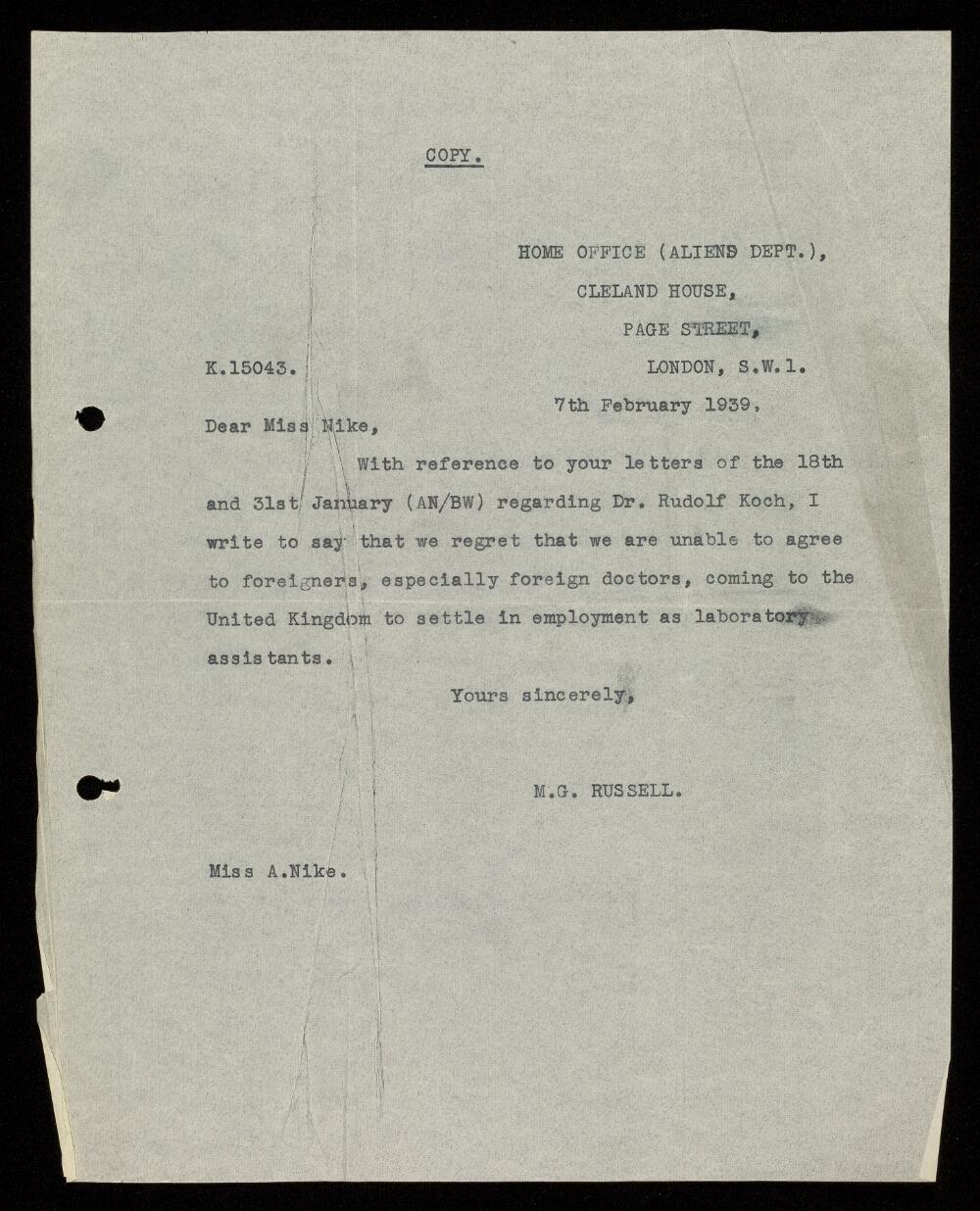

It is not entirely surprising that the inventory begins with “One large bible in folio”. The bible would have been a vital part of any 17th-century book collection, and the mention of its large size and format, as well as its relatively high value of 16 shillings, emphasises the primary importance of the scripture in Havelock’s collection. Moreover, the attention to its physicality reminds us that books were also objects to be valued for their aesthetic qualities. Next comes the most expensive book in the inventory, John Foxe’s influential Protestant martyrology called

Acts and Monuments (here referred to by its popular title,

The Book of Martyrs). This massive folio, full of distinctive woodcut illustrations, was given the value of £1 6s 8d - more than the price of the sword with a silver hilt that was among Havelock’s possessions at Berwick upon Tweed.

The ordering of the books in the inventory tells us a lot about the importance that was assigned to them. From these and other large-format works of theology and history, the inventory moves on through a mix of quartos and octavos, and finishes with an undifferentiated group of “83 little books besides” as well as a bag of songbooks. Whether or not this seemingly hierarchical arrangement was how Isaac Havelock organised the books in his house, we cannot know for sure. While inventories tended to reflect the layout of goods in a house, the historian Donald Spaeth has recently explored the ways that their order and arrangement could be dependent on the methods of individual appraisers or local conventions.

Woodcut illustration of the burning of John Rogers, the first victim of the Marian persecutions in England. From the first English edition of Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. (Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain)

The Bible and

Foxe’s Book of Martyrs are a fitting beginning to a list that paints a picture of someone well-read in a variety of Protestant writings. Havelock owned a range of works by important figures in the Reformation from across Europe. These included the works of William Tyndale, whose English translation of the Bible played an important role in the English Reformation; an edition of the New Testament by the French reformer Theodore Beza; the

Commonplaces of the Italian-born Peter Martyr Vermigli, a standard textbook of Reformed theology; and the

Meditations of the German Lutheran Johann Gerhard. He also owned a copy of

De civitate Dei by Saint Augustine, whose works had become popular among Protestant reformers.

In addition to these pan-European religious bestsellers, Havelock had had an interest in vernacular works of popular devotion. Among these were Lewis Bayly’s hugely popular religious self-help book

The Practice of Piety, John Norden’s A Poore Mans Rest, and treatises and sermons by the Puritan preachers William Cowper, Richard Stock and John Dod. He also possessed a copy of George Herbert’s collection of religious poetry,

The Temple. However, the inventory isn’t uniformly Protestant. Havelock owned

The Passions of The Mind, a treatise on the passions written by Thomas Wright. Wright, born in York to a Catholic family, was a Jesuit who had spent much of the 1590s imprisoned in York due to his recusant activity.

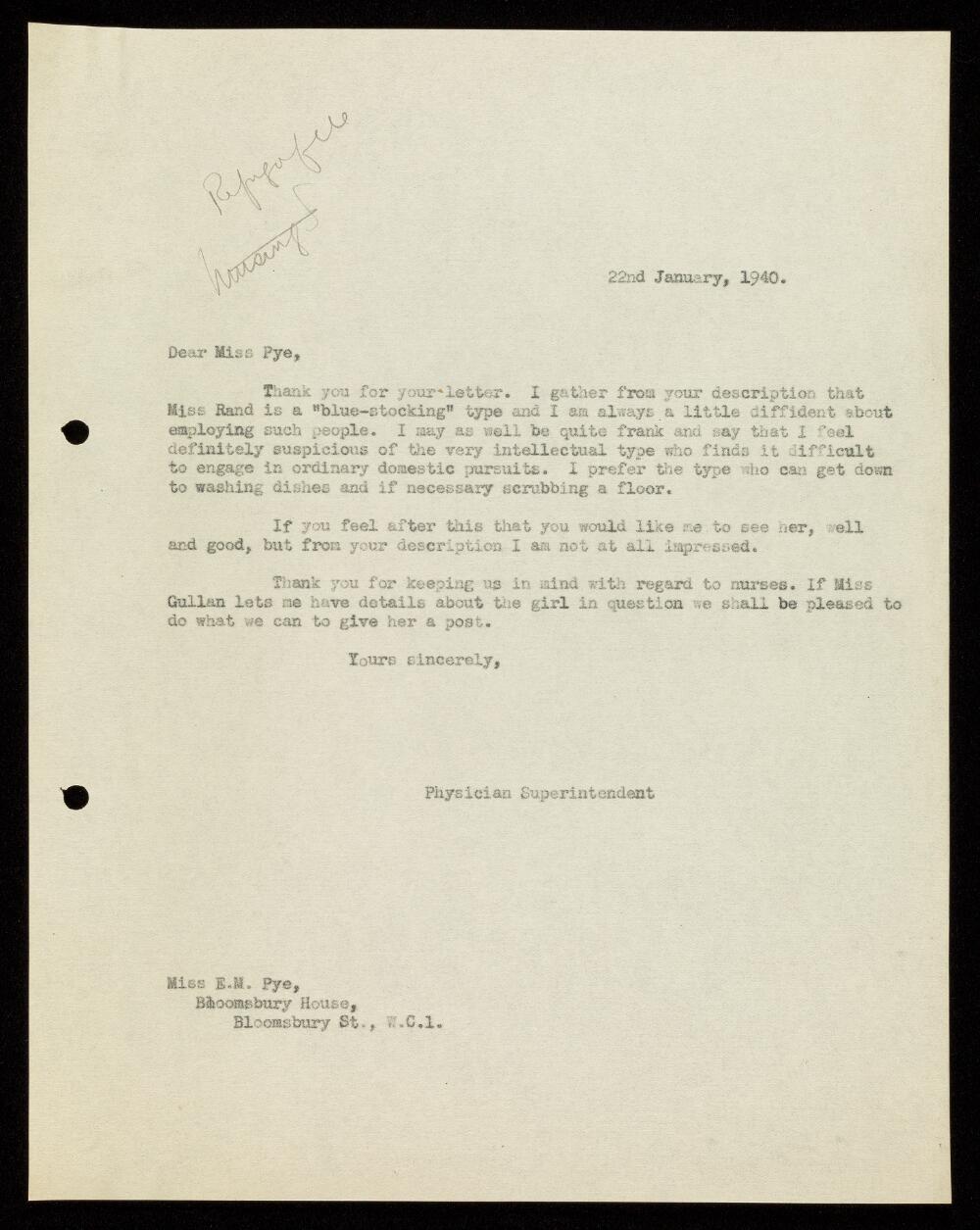

In the fore chamber of his house in York, the same room that contained his desk and writing materials, Havelock had a “large mapp”. As this is listed in the same entry as “a woodden frame with pictures”, it is tempting to imagine the map hanging on the wall above him as he sat writing, perhaps providing a window onto distant lands. From his books, it does seem that Havelock had a particular interest in travel and the world - and in particular the Middle East. His library contained Heinrich Bünting’s popular

Itinerarium Sacrae Scripturae, a book describing the geography and landscapes in which biblical events and journeys took place. He owned an account of the travels of George Sandys, son of Archbishop of York Edwin Sandys, which included a map of the Middle East along with lavish illustrations of Constantinople’s skyline, the Egyptian pyramids, and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. More sensational was an account of the travels of the Scotsman William Lithgow, whose journey by foot through Europe to the Middle East and North Africa purportedly involved daring escapes, shipwrecks and encounters with pirates.

A map of the holy land from the 1585 German edition of Heinrich Bünting’s Itinerarium Sacrae Scripturae. (Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain)

These travel narratives are complemented by other larger-scale works of world history and geography by John Swan, Peter Heylyn and Walter Raleigh. Together, their variety demonstrates that the early modern interest in the world wasn’t solely restricted to the category of knowledge we now call geography. These books ranged from biblical history to current affairs, carefully sourced scholarship to highly personal accounts, and indeed from fact to fiction - the authoritatively-titled

History of Trebizond in Havelock’s library was actually a collection of romances.

The rest of the inventory suggests that Havelock’s reading covered a wide range of subjects.

Law is well represented; he owned books of statutes and decrees, a manual on the role of justice of the peace, and the earliest treatise on women’s rights in English known as

The Womans Lawyer. He owned a large chronicle of British history from the Roman conquest, as well as two histories of the reign of Elizabeth I. An interest in Latin authors is suggested by a translation of the Roman historian Justin, a copy of what is likely to be Lucan’s epic poem on the Roman civil war, and a parallel translation of the

Distichs of Cato - a popular schoolbook for teaching Latin. We may also wonder about Havelock’s connection to music, as he owned a bible “with singing psalmes”, an

Introduction to Practicall Musicke by the composer of madrigals Thomas Morley, and a bag of songbooks valued at a pound - although there is no mention of any instruments in his possession.

Where would Havelock have got these books from? At the time of his death, no books had been printed in York for more than a hundred years, and it would be another two before King Charles brought the royal printer to York at the onset of civil war. Rather, Havelock’s library was made up of books printed in the centres of the early seventeenth-century print trade in Britain. Most came from London, a number from the two university cities Oxford and Cambridge, and at least one of his books was printed in Edinburgh.

However, he wouldn’t have needed to travel far to get his hands on them. York was part of an impressive distribution network for books that stretched across the country and beyond, and the Minster Yard was home to a number of booksellers, bookbinders and stationers. The inventory of John Foster, the owner of one of these shops who died in 1616, attests to the scale of the trade. His stock included three and a half thousand copies of over a thousand titles, with books printed as far away as Venice, Zurich and Lyon. In fact, a number of books in Havelock’s inventory match titles that were on sale in Foster’s shop, suggesting he may have been a regular customer.

Can this list of books tell us who Isaac Havelock was? The inventory gives us an impression of a wealthy protestant reader, who was buying books well into the last decade of his life: a man who was interested in the wider world, history, and law. His library, writing equipment and the “3 dozen of parchment skinns” listed alongside his books suggest that literacy was an important part of his profession. He may have been involved in music-making, either in connection with the Minster or one of York’s many other churches.

However, there are also significant gaps in the information provided - what were the 83 “little books besides” that the appraisers didn’t list by name? Nor does the inventory tell us anything about the social lives of the books. Reading was frequently a social activity as books were read aloud or passed among friends, but we cannot know about the other women or men who interacted with Havelock’s library. Finally, we all know that the books on our bookshelves can mean different things to us. Some we buy for pleasure, others profit. Some we read once, others we return to time and time again. Some books change our way of looking at the world, others reinforce what we already believe. The book historian David Pearson entreats us to bear this in mind when researching books and their readers: “We should think of these libraries not so much as mirrors of the particular interests of their owners, but more as platforms or springboards from which their own ideas and perceptions of the world developed” (2010: 159). Nonetheless, Isaac Havelock’s inventory offers a remarkable insight into seventeenth-century York’s literary world.