As we get ready to celebrate the coronation of King Charles III this weekend, our guest blogger Helen Watt investigates an intriguing set of entries relating to a past coronation, which she found in one of our medieval Archbishops' registers during a recent project.

On 6 May 2023, Charles,

formerly Prince of Wales, will be crowned King Charles III, following the death

of his mother, Queen Elizabeth II, last year. The coronation ceremony will take

place in Westminster Abbey, where kings and queens of England have been crowned

since 1066. Although King Charles is intending to have a shorter ceremony than

that of his mother in 1953, the solemnities will presumably still largely follow

that same order of service which has been used for English royal coronations

since the fourteenth century. Details are found in the Liber Regalis, an

illuminated manuscript belonging to the Abbey, thought to have been created

around 1382, probably for the coronation of Queen Anne of Bohemia, the first

wife of King Richard II.

|

| Cover of a programme for the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, 1953, from the author's own family papers. |

The Liber Regalis shows

that the coronation ceremony is performed by the archbishop of Canterbury, with

the bishop of Durham and the bishop of Bath and Wells as supporters of the new

monarch. What then was the role of the archbishop of York in the proceedings?

No particular actions by him are mentioned in the order of service and it seems

likely that the archbishop at the time would simply have been present as the

second highest-ranking member of the clergy alongside the archbishop of

Canterbury. So it is all the more intriguing to find the order of service for

the coronation of a king in the register of Alexander Neville, archbishop of

York, 1374-1388, ‘Ordo coronandi Regem’ (Order of crowning a king).

This entry is found alongside two others relating to the coronation of King

Richard II and a third relating to the manner of performing the coronation of a

king and queen, ‘Qua solemp[nita]te ac sub q[ui]buz m[od]o & for[m]a Rex

& Regina debeant coronari’ (By which solemnity and under what manner

and form a king and queen should be crowned).

All four entries have come to light following successive projects to work on

the registers of the Archbishops of York, 1225-1650, carried out by the Borthwick

Institute for Archives and Department of History at the University of York. The

first of these projects, entitled ‘Archbishops’ Registers Revealed’, completed

between 2014 and 2015 in the Borthwick and generously funded by the Andrew W.

Mellon Foundation, resulted in the digitisation of the registers of the

Archbishops of York, 1225-1650.

It produced high quality images of the registers contained in an online

database and included entries from the register of Archbishop Neville, which

had been indexed as part of the pilot for the project in 2012, also funded by

the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

Following on from that project and a subsequent project generously funded by

the Marc Fitch Fund also carried out in the Borthwick between 2015 and 2016 to

index the registers, 1576-1650, ‘The Northern Way’ project, generously funded

by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, ran from 2019 to 2022 and was managed

by the Department of History in partnership with The National Archives, Kew,

and with the support of York Minster.

That project carried out indexing of all the fourteenth century York

Archbishops’ registers, and so further highlighted entries from Neville’s

registers, including those relating to the coronation of Richard II and the

order of service for coronations of a king and a king and queen.

|

| Registers of Archbishop Neville on the shelves in the Borthwick strongroom, 2023. |

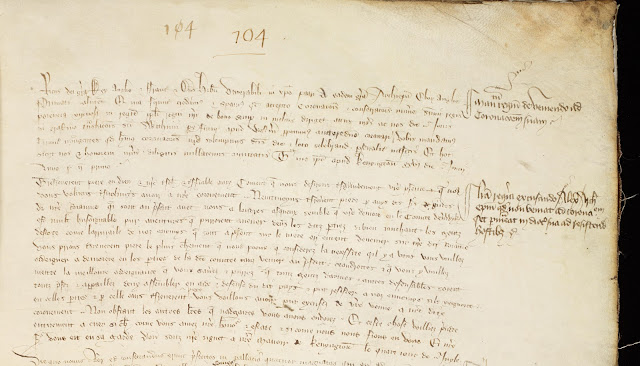

|

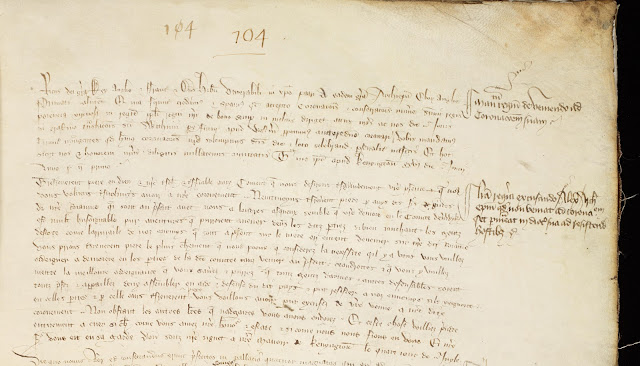

The register of Archbishop Neville containing entries for the coronation of King Richard II.

|

Thinking of the latter two

entries and taking into account the duration of the reign of Richard II, 1377-1399,

and the period during which Neville was archbishop, 1374-1388, could the first

entry relate to the coronation of Richard II in 1377 and predate the Liber

Regalis, and the second, to the coronation of Richard II’s queen in

1382 and follow the Liber Regalis? As we shall see, the answer is not so

simple. The first point to consider is that the initial entry firmly

identifiable with the coronation of Richard II consists of the royal order to

the archbishop, dated 26 June 1377, to attend that coronation, which was to

take place on 16 July 1377 at Westminster Abbey. This order is identical to

that sent out to the archbishop of Canterbury and presumably to all those dignitaries

who were to attend.

However, the second entry in the register consists of a royal letter dated 4

July 1377, excusing Archbishop Neville from attending, for fear of invasions by

the Scots and enemies approaching by sea. These reasons seem to make it very

plausible that the archbishop would not travel to London at that time;

nevertheless he is described as only ever having left his archdiocese during

his first ten years in office, mostly for short spaces at a time to attend Parliament.

The only other period he spent outside his own diocese was to assist in

defending the border with Scotland during threats of invasions in 1383 and

1384, and not in 1377.

Although taxation, specifically two clerical tenths from Canterbury and York,

was to be raised at the very beginning of the reign of Richard II to finance resisting

enemy invasions, this request may well have applied equally to naval attacks

launched by the French, as to invasions by the Scots.

Therefore, it seems very likely that Archbishop Neville was simply not intending

to make the journey to London for the coronation, but to stay in the north,

probably at his palace at Cawood, on which he spent much time and money

improving.

|

| The first two entries relating to the coronation from the register of Archbishop Neville: the Royal writ of King Richard II ordering the archbishop of York to attend his coronation on 16 July 1377 at Westminster, and copy of a letter of Richard II excusing the archbishop from attending his coronation. |

Following the royal order and

letter are the two entries relating to the order of service for the coronation

of a king and of a king and queen, as already mentioned. These entries are

undated, but are preceded by those noted above, dated in 1377, and followed by

others, also dated in 1377, although not in strict date order.

Does this order in the register suggest that the entries relating to the

coronation service also date from 1377 and so pre-date the coronation of Queen

Anne of Bohemia? If not, could they have been copied into the register, but not

in chronological order? One answer to these questions might be to look at the

overall makeup of the register; as with most of the fourteenth-century

registers of the Archbishops of York, it is divided into various sections and

these entries fall within the section entitled ‘Diverse Letters’. This section

contains entries, as the title suggests, covering a range of subjects, but

generally dated between 1377 and 1384. Certainly, the first few folios of this

section, ff. 100-7, including f. 104 in which the entries relating to the

coronation are found, do appear to be arranged in chronological order between

1377 and 1382, although f. 105r includes an entry containing a copy of a

document dated in 1222, and f. 107r, an entry dated in May 1378, in between

others dated in 1381 and 1382, therefore perhaps out of place. Given this

general arrangement, it is possible to conclude that the coronation entries,

because they appear between entries dated in 1377, may well pre-date 1382, and

so perhaps relate to an earlier period, perhaps to 1377 or before.

|

| Entries relating to the order of service for the coronation of a king and of a king and queen, found in the register of Archbishop Neville, c.1377. |

Turning back to the Liber

Regalis, as well as existing in manuscript form, as described above, and as

well as having been printed in volume 93 of the series of publications of the

Roxburghe Club, the

manuscript also appears in print, in the original Latin with an English translation,

alongside several other documents relating to coronations of English kings and

queens in another volume, English Coronation Records.

Therefore, these two works provide ample means of comparing the text of the Liber

Regalis with the entries found in Archbishop Neville’s register, in an

attempt to discover the origin of the register entries. The editor of English

Coronation Records also provides details of the recensions, or various

forms which the medieval coronation service took and describes the Liber

Regalis as the fourth recension of the text, the fullest thus far.

The editor was also of the opinion that this particular version was used at the

coronation of King Edward II, which took place in 1308, but only contained

short rubrics or criteria for the service, with more detail included later,

perhaps in the reign of Richard II.

Could this identification of

the text of the Liber Regalis provide further corroboration of the date

of the entries in the archbishop’s register or not? The only way to find out

was to compare the entries with the text of the Liber Regalis, line by

line and word for word. This exercise proved very fruitful and although it

answers the question in part, also raises other points. The results of the

comparison appear to confirm that the register entries only contain the short

rubrics of the coronation service, whereas the Liber Regalis is a much

fuller version of the text. Therefore, it does seem likely that the register

entries predate the more detailed order of service used in the coronation of

Anne of Bohemia, but by how much? The editor of English Coronation Records

also compared the Liber Regalis with another document, a fourteenth-century

Pontifical of Westminster Abbey in the Bodleian Library in Oxford.

Looking at the variations in the text of the Liber Regalis found in the

Westminster Pontifical, it is clear that the entries in the York archbishop’s

register follow those variations very closely, if not exactly, and so the

entries must pre-date the Liber Regalis. Indeed, the editor of a text for

a coronation order of service printed in another volume, Monumenta Ritualia

Ecclesiae Anglicanae, specifically identifies the Westminster Pontifical

variations as relating to the order of service for Edward II.

However, also published in English Coronation Records is a document

entitled ‘Forma et Modus’, which is said to be reminiscent of the rubrics of

the Liber Regalis, but is thought to date from the fifteenth century.

Although the first register entry relating to the coronation contains the words

‘m[od]o & for[m]a’, as noted above, so that the same words appear in the

title and heading of each, the texts do not match and so the register entry may

still relate to an earlier period.

Nevertheless, the register

entries appear to have been copied from another text, since there are evidently

copying errors, where the scribe has missed a line, realised his mistake,

crossed out a few words and started again.

Another aspect of the register entries is that when compared with the Liber

Regalis, they are not in order, but that the first of the entries, relating

to the coronation of a king and queen, noted above, should fall within the

second, relating to the coronation of a king.

Could it be possible that the

register entries were copied from a manuscript belonging to Westminster Abbey,

containing details of the order of service of the coronation, probably for

Edward II, and if so, how and why? If Archbishop Neville rarely left his

archdiocese, did his clerks also stay with him in the north or have access to

manuscripts in the south? Or were there other manuscripts in York archdiocese

containing the recension of the coronation service earlier than that fuller

version thought to have been produced during the reign of Richard II? If the

archbishop had no intention of attending the coronation ceremony, why was the

order of service copied into his register together with the other documents in

the first place? At present, all these questions are intriguing and remain

unanswered, but still show that there was perhaps the same interest in the

coronation of a new king in the late fourteenth century as there will be today.

See F. D. Logan (ed.),

‘The Register of Simon Sudbury, Archbishop of Canterbury, 1375-1381’, Canterbury

and York Society, 110 (Woodbridge, 2020), p. 293, no. 798.

R. G. Davies,

‘Alexander Neville, Archbishop of York, 1374-1388’, Yorkshire Archaeological

Journal, 47 (1975), 87-101 (93).

L. G. Wickham Legg

(ed.), English Coronation Records (Westminster, 1901), XIII, pp. 81-130.