*************************************

One of the pleasures of digitising an archive like that of The Retreat, is the number of throwaway comments and random snippets which refer to bigger events in the history of Britain and the world. The correspondence files are particularly rich in this regard, and offer a fascinating insight into life during history’s “Big Events”, through the eyes of people who were there at the time. This blog will pick out a few of my favourite examples, although there are many more among the thousands of digitised documents from this archive which can be found online by browsing our catalogue.

The Tooley Street Fire

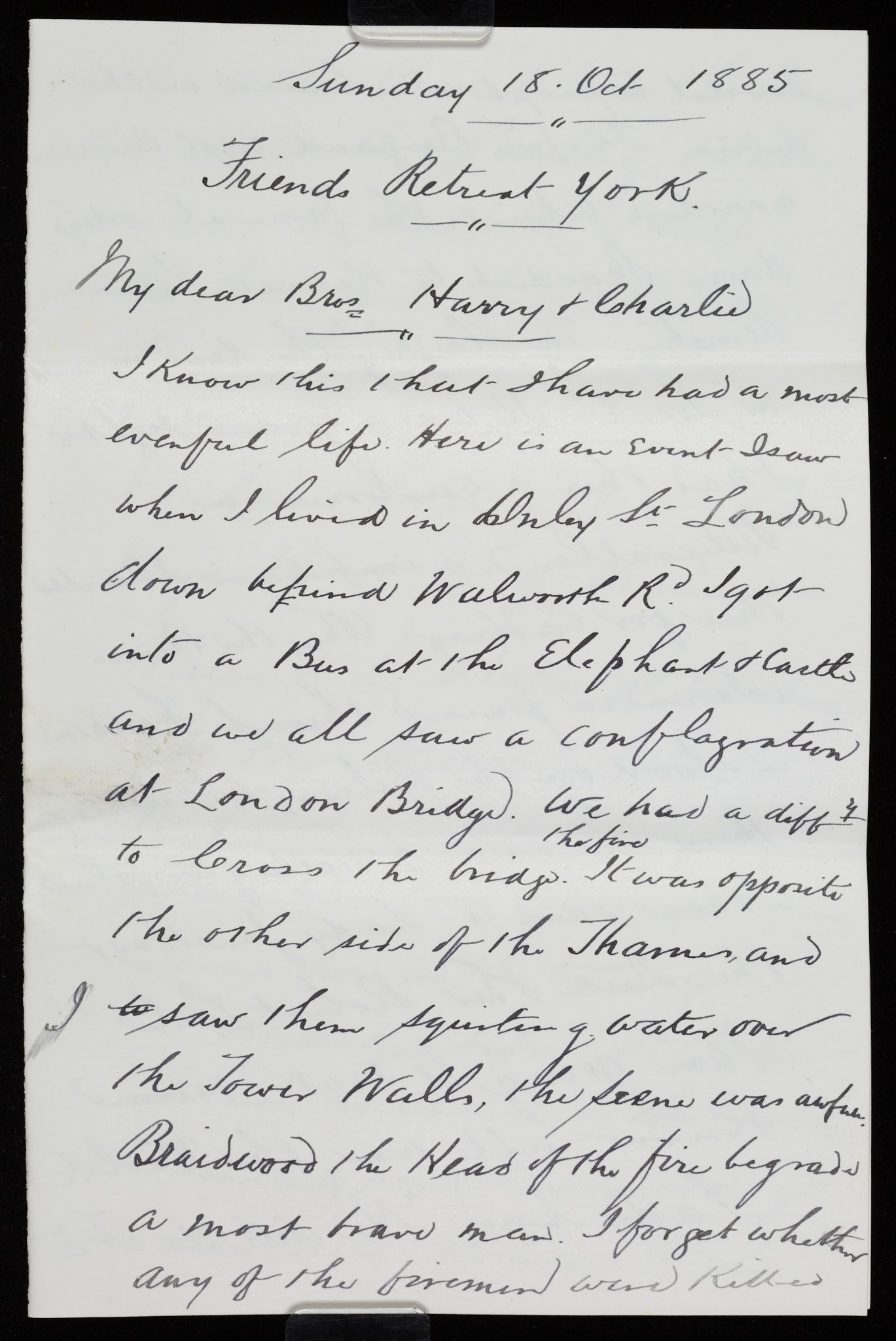

Writing in 1885, Mr Charles Cave Wilmott, a patient at The Retreat, recalled one of his experiences as a London resident earlier in his life:

|

| RET/6/19/1 |

“I got into a Bus and at the Elephant & Castle and we all saw a conflagration at London Bridge. We had a diffy to Cross the bridge. The fire It was opposite the other side of the Thames, and I to saw them squirting water over the Tower Walls, the scene was awfull [sic]. Braidwood the Head of the fire begrade [sic] a most brave man. I forget whether any of the firemen were killed several bu people were buried in the debris. The fire Brigade with Braidwood marched behind the funeral cortege down Shoreditch to Kensall Green Semetry [sic], The playing the dead march in Saul. It was a grand sight.”

This memory has many parallels with the Tooley Street Fire of 1861, which was often referred to as the greatest fire since the Great Fire of London. This took place in the warehouses which lined the Thames close to London Bridge and took two weeks to extinguish. As with other disasters in the Victorian city, the Tooley Street Fire drew crowds of over 30,000 people, standing on the bridge and the opposite side of the river, bringing traffic to a standstill, and accounting for the difficulty which Mr Wilmott’s bus experienced in crossing. James Braidwood, the Superintendent of the London Fire Engine Establishment, was in fact killed during the effort to extinguish this conflagration, buried under a wall which collapsed on him as he was attempting to assist one of his firemen. A funeral cortege like the one Mr Wilmott remembered , a mile and a half long, carried Braidwood to his final resting place. This event was a major spur for the creation of the Metropolitan Fire Brigade in 1866.

The First World War

Day to day history is also captured in vivid detail in the Retreat Archive. The First World War had a greater impact on everyday life in Britain than any previous war. For the first time, war was on the doorstep, and it’s effects can be seen everywhere in correspondence dating from 1914 to 1918. This led to the issuing of new rules and regulations which would govern people’s lives, and a level of fear began to affect even the most mundane of interactions with strangers.

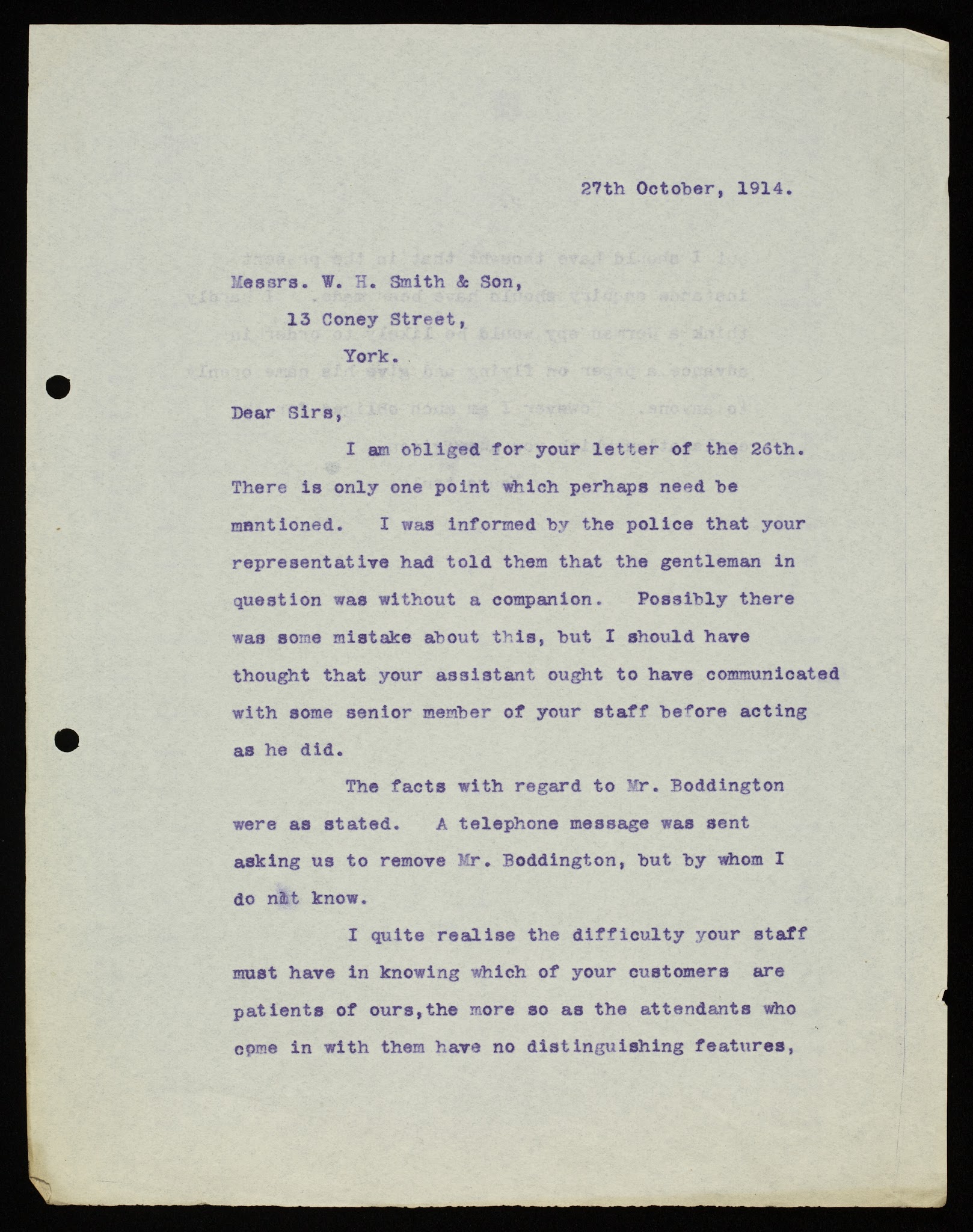

Take, for example, the case of Harold Schluter, a patient at The Retreat in 1914. While shopping in York, he entered a branch of WHSmith to order a book on flight, and was promptly reported to the police by the shop assistant on suspicion of being a German spy.

A letter from WHSmith justifying the action of the assistant stated that "as the name was distinctly German, the paper in question was 'Flight' and apparently the address of the customer unknown, he considered on the account of the warning issued within the last few days, that he had a public duty to perform"

|

| RET/6/20/1/18/12 |

As was drily noted in the Retreat’s response to the shop’s apology: “I hardly think a German Spy would be likely to order in advance a paper on flying and give his name openly to anyone.”

|

| RET/6/20/1/18/12 |

The First World War was a difficult issue for members of the Society of Friends, like Dr Bedford Pierce, the Superintendent of the Retreat. Correspondence from 1914-1918 is littered with references to the War, to conscription, and to the problems arising from being a committed pacifist, but also feeling a deep sense of loyalty towards Britain.

In a letter to a friend, dated 27th February 1918, Dr Pierce wrote: "I am interested in hearing about your son going out. I fear it will be an anxious time for you. One cannot but feel that this year the promise of spring is hateful. It would be much more encouraging if there was a little prospect of an end to it, but if the settlement is by fighting it will be a long time before the conclusion is reached.” This links to the feelings of many members of the Society of Friends, who felt that Germany and her allies represented an evil which must be resisted, but that fighting was not the answer.

Dr Pierce was often asked to allow patients to present themselves for medical inspection by the army doctors in order to see whether they could be judged fit to join up and fight. In some cases, this was allowed for the patient’s own peace of mind, despite the fact that they would almost certainly be judged unfit due to their mental or physical conditions; some patients suffered great distress at the thought that they had not volunteered to serve their country. As a result of this suffering, which could exacerbate existing mental illnesses like depression, or delusions of having committed a great sin by damaging self-esteem, Dr Pierce often arranged for patients to see army medical officers to be examined, producing a flurry of correspondence with family and friends.

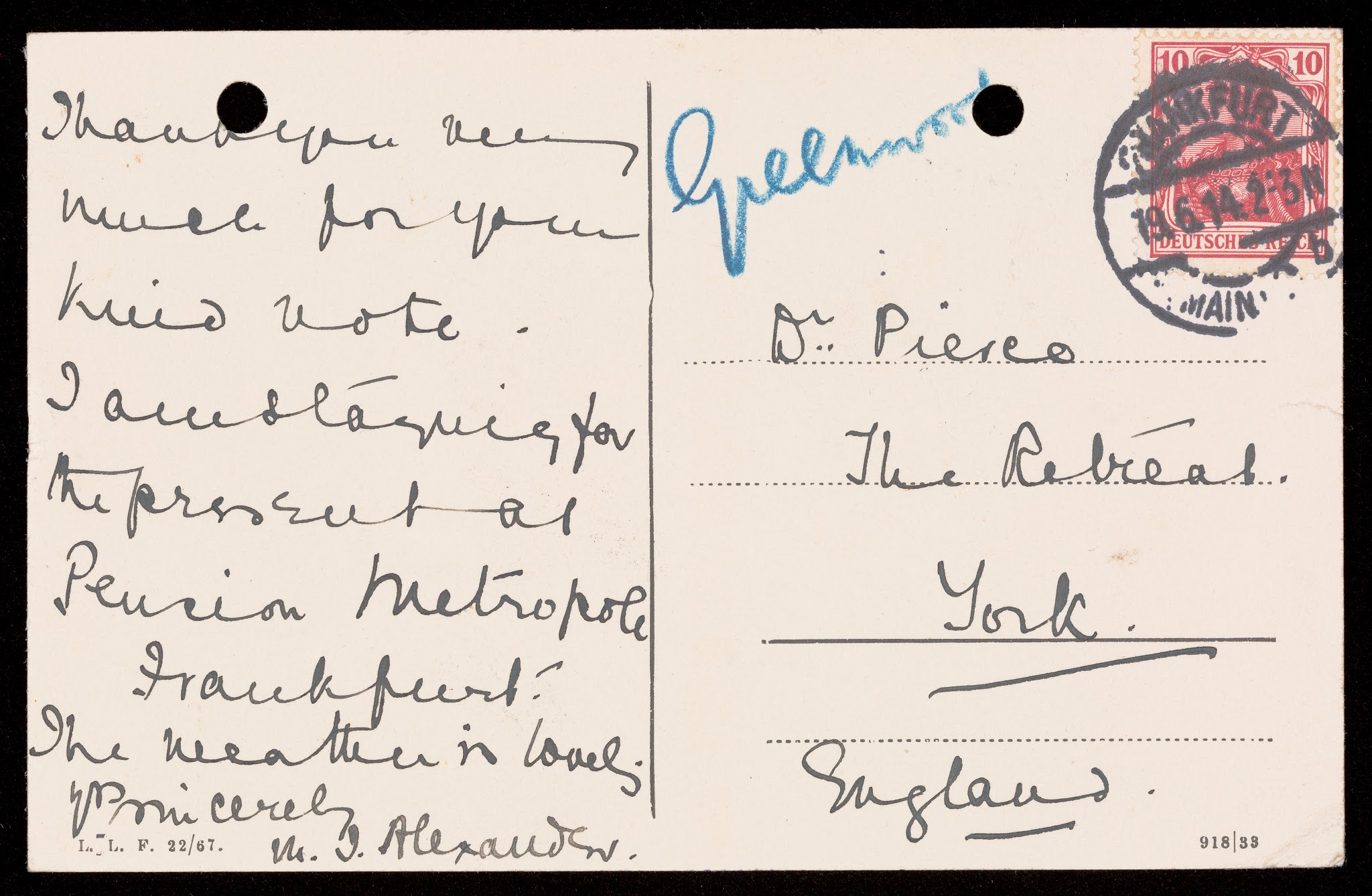

Another document in this archive shows the calm before the storm of the First World War from a different perspective.

|

| RET/6/20/1/7/35 |

This postcard, dated just two weeks before the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the event which is often described as the final spark to the tinderbox of conditions which existed before the First World War, was sent from Frankfurt. There is no sign in the sunny photograph of any dark clouds on the horizon. The postcard’s sender writes:

|

| RET/6/20/1/7/35 |

“Thankyou very much for your kind note. I am staying for the present at Pension Metropole Frankfurt. The weather is lovely.”

Technology in the Home

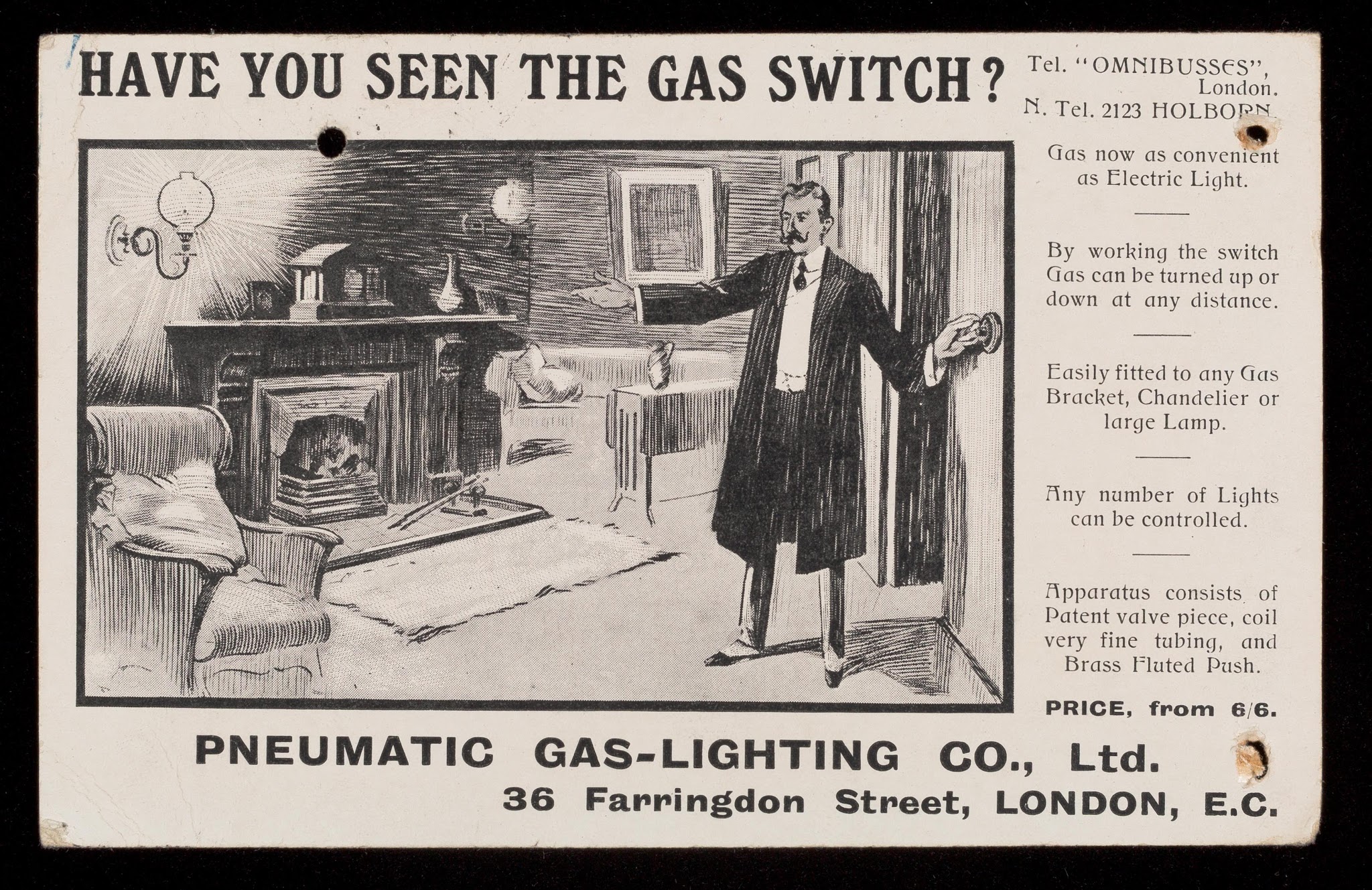

The Retreat Archive also offers a view of a world of rapid technological advance, with recognisable innovations that we still use in some form today, as well as some which never quite caught on.

|

| RET/3/3/2/16 |

The competition between gas and electric lighting in the home is captured in this advertisement of 1906/7, which declares that gas was “now as convenient as Electric Light”. In the twenty-first century, with almost ubiquitous electric lighting, it seems odd to remember that this was by no means a foregone conclusion, and that the struggle between electricity and gas companies was fiercely competitive.

|

| RET/4/3/1/1 |

Another invention which we can recognise today is the dishwasher, but this one, advertised in 1921 seems very large and complex by today’s standards. The advert confidently declares that the “Channel Race” Patent Crockery Washer is “A machine you will eventually buy.”

The early twentieth century produced a wealth of labour-saving devices for domestic use, as the era of the domestic servant came to a close. After the First World War, women who had taken on work which had previously been the preserve of men often wanted to continue working rather than return to domestic service. Although many women lost their wartime jobs in favour of men returning from the fighting, the world of work, and attitudes to female labour both inside and outside the home had changed forever.

These are just a few of the topics, relating to wider themes in history, which can be accessed through the archives of The Retreat.

More information about the Wellcome Library funded project to digitise the Retreat archive can be found on the project pages of our website. Digital surrogates from the Retreat archive project are available via the Wellcome Library and can also be found by following the links from the Retreat catalogue.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.